In the early modern era, scores of impoverished individuals, groups, and even penniless families migrated across the roads and streets of Europe. They travelled from region to region in search of work or charity. Among these wandering migrants were downtrodden Jews. Their stories usually do not appear in the archives. The exceptions are the miserable souls who ran into trouble: Jews who were arrested, imprisoned and brought before judges to face trial.

Such was the case in the city of Frankfurt in 1714, which back then was already a bustling urban center, full of opportunity and industry. There was a well-known, established Jewish community in the city which owed its status to, among other things, its well-groomed relationship with the Holy Roman Emperors (in other words, the German emperors) as well as the abundance of employment opportunities available.

Poor, wandering Jews knew that they could find food, shelter, and charity in Frankfurt because of the generosity of its Jewish residents. At times, the wandering Jews socialized with the poor locals, who at least benefited from being members of the community.

This may have been the background setting for the events of the summer of 1714, when a gang of at least four Jews burst into the shop of a Christian clothes merchant named Maria Elizabeth Lochmann. The widow Lochmann ran a thriving business. Her shop was located in Frankfurt’s city center, already known for its valuable real-estate, and the loot from the burglary was reported to be 2,500 florins, a very high sum of money at the time. The circumstantial evidence was documented in a criminal case brought against the thieves and is preserved in the archives of the municipality of Frankfurt to this day.

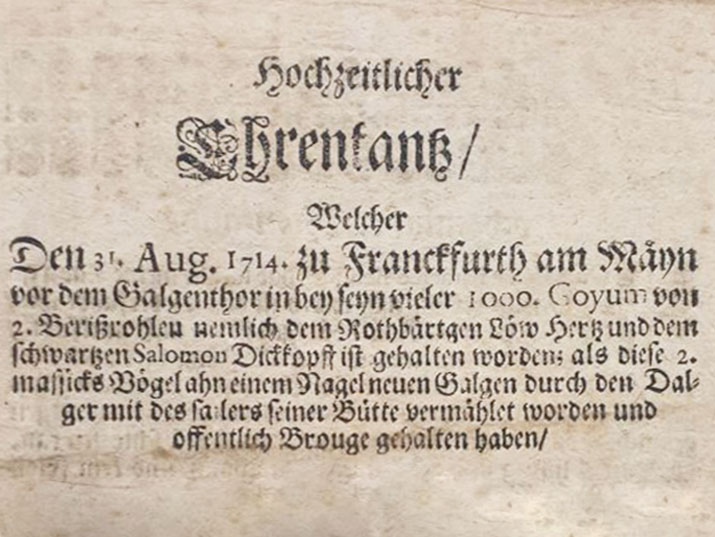

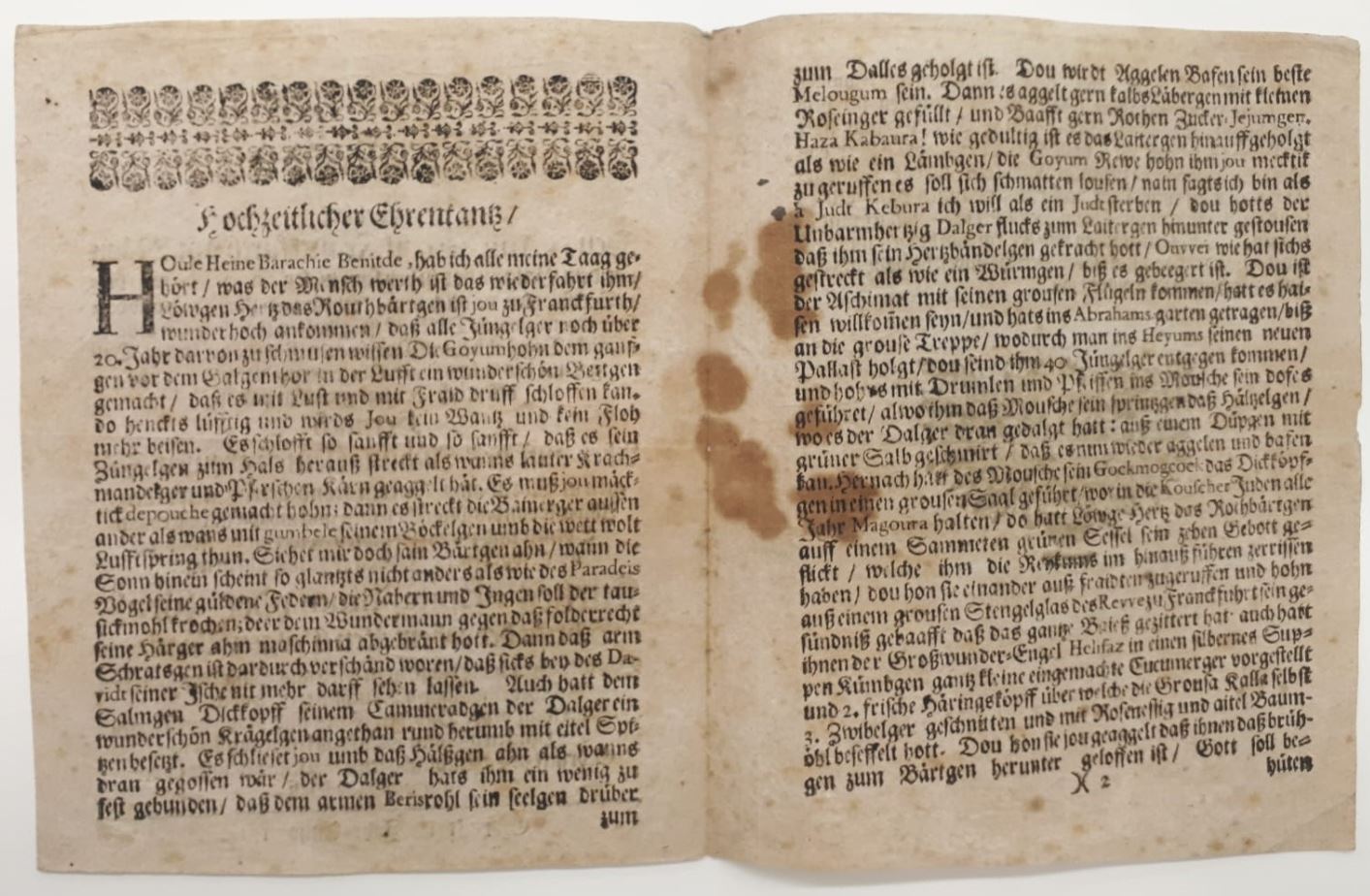

But, there is another document that details the affair, which resulted in the execution of two of the accused Jews. In August 2018, the National Library purchased a very rare item at an auction: an anti-Semitic pamphlet that ridiculed the two Jews who were, ultimately, executed. One was named Lev Hertz (apparently a resident of Frankfurt). The second was named as Solomon Dickkopf (the surname means “thick head”). The four pages of this satirical anti-Semitic text detail the final moments of the two thieves’ lives. The anonymous author was undoubtedly familiar with Jews, their customs and their style of speech and subjected these to twisted mockery in his work. He described the execution of the two as a “wedding” between the condemned men and the new gallows which had been erected outside the city walls.

The pamphlet purchased at auction by the National Library is quite rare. The only other known copy is found in the criminal files of the Frankfurt city archives. A number of details in the pamphlet indicate that the precise documentation of the crime was of little interest to the author. It makes no mention of the reasons for the execution (the theft) and also ignores the fact that the other two participants were apparently given only minimal punishments.

A curious detail appears at the bottom of the pamphlet’s first page, where we find the name of the printer, Veit Schnitzler, and the town in which it was printed, Katzenelnbogen (west of Frankfurt). However, we know of no printing presses owned by a man of this name. A logical conclusion that can be drawn from this is that “Veit Schnitzler” was actually a fictitious name that was chosen in order to hide the true source of the text.

It is possible that the author feared that the Jewish community would press charges against him for the abhorrent content of the pamphlet. A similar situation had occurred several years earlier, when the Jewish community sued anti-Semitic author Johann Andreas Eisenmenger. Eisenmenger had authored a book referred to in short as “Judaism Unveiled” (the publication’s full name was: “Judaism Unveiled, a thorough and genuine account of the horrific manner in which the stubborn Jews sully the Holy Trinity and disgrace it”). The Jewish community of Frankfurt successfully blocked the publication of the book in the Holy Roman Empire because of its well-established relations with the imperial court.

In 1734, nearly twenty years after the affair, additional information was published about the incident in a historical chronicle. The author, Georg August von Lersner, mentions the hanging of two Jews on the 31st of August, 1714. According to von Lersner’s account, the authorities ordered that the bodies not be taken down following the execution. They wanted them to remain hanging as a warning to any other would-be thieves. But, on the night of November 14th, the bodies were removed without authorization. The identities of the perpetrators were never discovered. Von Lersner took the liberty to assume that it was another thief, but it could just as well have been a gesture of decency by local Jews in order to recover the bodies of their brethren for the sake of a proper Jewish burial.

This article was written in collaboration with Dr. Verena Kasper-Marienberg, an expert in the field of the Frankfurt Jewry.

If you liked this article, try these:

The Jew Who Fought Against the Censors of the Inquisition

Rare Items: A Glimpse into the Lives of Max Nordau and His Only Daughter, Maxa

The Jewish Lawyer Who Drafted the Constitution of the Weimar Republic