Fragments of manuscripts discovered in book bindings often bring exciting surprises, serving as a telling reminder of how crucial a little bit of luck can be in this field. Professor Simcha Emanuel has extensively researched the subject of manuscript fragments repurposed to cover books or archival documents in his two-volume work, Hidden Treasures from Europe.

Here, however, I want to focus on a slightly different phenomenon: the use of old religious texts in book bindings. I’ve written before about the common practice of repurposing worn-out pages from sacred Jewish texts to create bindings. Now, I want to share a fascinating new discovery.

It relates to a manuscript known as New York – Lehmann BR 189. A copy of this manuscript had been part of the National Library of Israel’s collection since 2001, preserved on microfilm (No. 72564). The catalog entry briefly described it as a commentary on Rashi’s interpretation of the Torah, written in Ashkenazi script. That was all. But analyzing a manuscript from a black-and-white photocopy—especially without knowing its provenance—is challenging.

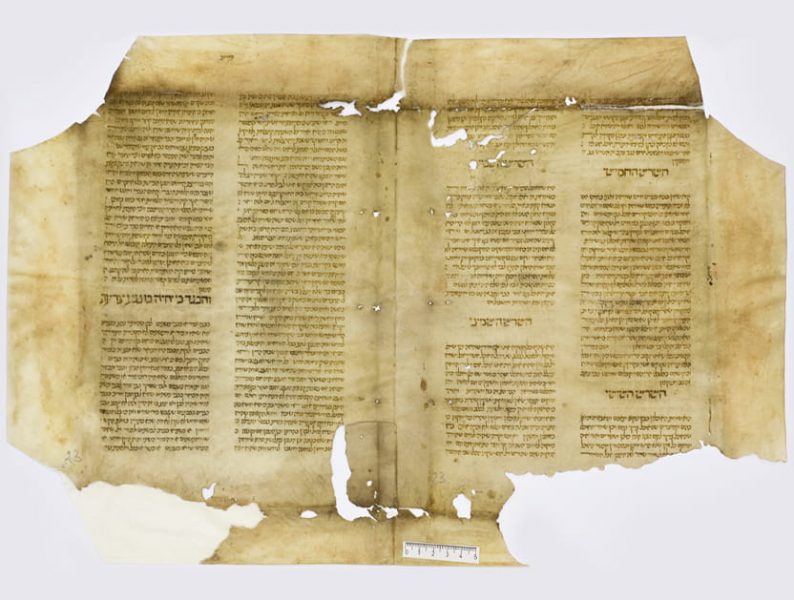

Last year, with the arrival of the Lehmann Collection at the National Library, I was finally able to examine the manuscript firsthand. The way its pages were cut, along with remnants of adhesive, clearly indicated that these leaves had once been part of a book binding. At some point, after the manuscript had outlived its original use—either due to wear or for some other reason—its pages were cut apart and glued together to form the cover of another book. Many years later, the binding was dismantled, the pages were separated once again, and the manuscript was restored to its original form. What an incredible stroke of luck!

This manuscript contains a commentary on Rashi’s Torah interpretation, focusing exclusively on linguistic aspects. A search in Otzar HaHochma (a comprehensive Jewish text database) revealed that this commentary was printed in Italy in 1560 in the town of Riva di Trento, under the title Dikdukei Rashi (Grammatical Analysis of Rashi), with no author credited.

Riva di Trento, now known as Riva del Garda, was home to a Jewish printing press. The history of this press is thoroughly documented in Meir Benayahu’s book Hebrew Printing at Cremona (Jerusalem, 1971), particularly in its fifth chapter.

Until now, the printed edition was the only known record of this work—no manuscript copies were thought to exist. Comparing our manuscript with the printed version confirmed that it was not copied from the published text. The manuscript contains numerous German words, labeled as “in the Ashkenazi tongue” (* בל”א – בלשון אשכנז*), which were omitted in the printed version. These omissions disrupted the textual flow, making the published commentary appear more awkward and difficult to follow.

The use of German also challenges the previous assumption that the book’s author was Rabbi Elijah Mizrachi (Re’em) of Turkey. Instead, it strengthens the case for Rabbi Elijah Levita, better known as Elijah Bachur, a renowned Ashkenazi grammarian.

A handwritten note in an old copy of Dikdukei Rashi, formerly housed in the Livorno Talmud Torah Library (and now digitized in Otzar HaChochma), attributes the book to Rabbi Elijah Halevi Ashkenazi:

“Compiled by the great grammarian, Rabbi Elijah Halevi Ashkenazi, of blessed memory. See his book Sefer HaBachur, Third Treatise, Principle 11, where he writes: ‘I had intended to compile another book in which I would explain all of Rashi’s grammatical interpretations in his biblical commentary.’”

Rabbi Elijah Levita (1469–1549), known as Elijah Bachur, was a prolific Hebrew linguist who authored numerous works. The frequent use of German phrases throughout the manuscript aligns with his style in other known texts. Furthermore, in Sefer HaBachur, he explicitly mentions his intention to write a commentary on Rashi—precisely the subject of Dikdukei Rashi.

Since Sefer HaBachur was written in 1517, this places Dikdukei Rashi sometime after that date. Initially, I believed the manuscript dated to the latter half of the 15th century, based on watermark evidence (featuring scissors and scales, a common motif from that period). However, given the strong case for Rabbi Elijah Bachur’s authorship—and the somewhat ambiguous nature of the watermark evidence—I now believe the manuscript belongs to the first half of the 16th century.

Recently, a contributor to the Otzar HaChochma forum, under the username “Yishar Koach,” conducted independent research into the book’s authorship. He concluded that Dikdukei Rashi was created in the 15th century and that its attribution to Elijah Bachur is incorrect.

He identified two passages where the author cites Rabbi Israel Bruna in the present tense, suggesting a personal acquaintance. Since Rabbi Bruna passed away around 1480, Elijah Bachur—who was only eleven years old at the time—could not have been the author.

This is a compelling argument. However, since our manuscript is missing the relevant pages, the question of authorship remains unresolved and requires further study. You can read Yishar Koach‘s detailed research here.

Regardless of its authorship, the survival of this rare manuscript is extraordinary. Had it been discarded in a genizah (a repository for worn-out sacred texts), it might never have been preserved. Had it not been repurposed as binding material, it may have disintegrated over time. Had an inquisitive antique dealer not dismantled the binding, its contents might have remained hidden forever.

And finally, without modern digital tools like Otzar HaHochma, we might never have identified what we were holding in our hands.