Who wouldn’t want to read from a Megillah they illustrated themselves for Purim?

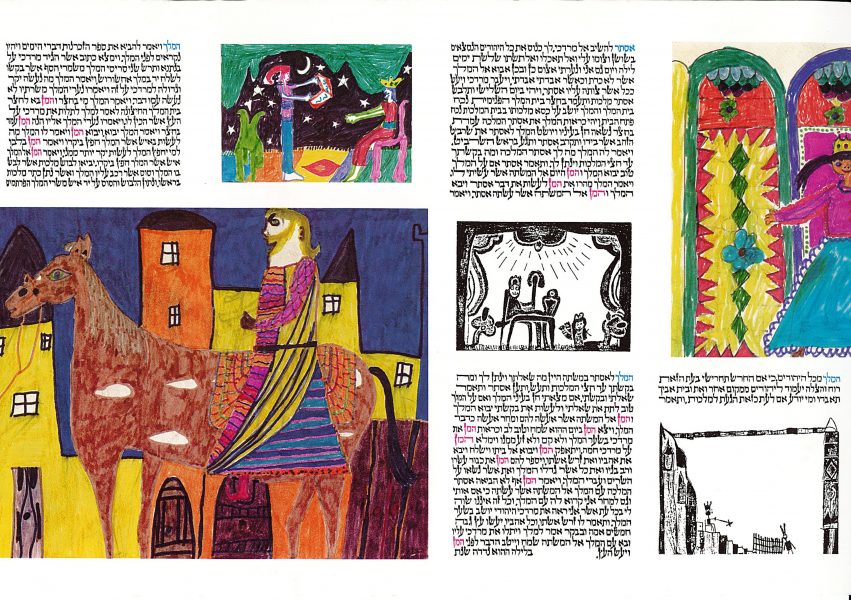

Take a look at this timeless Esther Scroll—illustrated decades ago by children who are now in their fifties, yet many still keep a copy at home. The scroll is captivating—the vivid colors and innocent drawings perfectly convey the dramatic story of Purim. Two copies of this special edition have found their way to the National Library of Israel.

But where did the idea of having children illustrate a Megillah—one intended for publication and distribution rather than just a family project—originate?

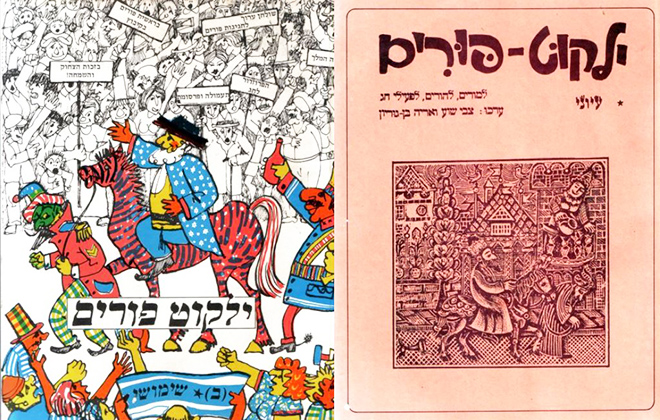

This unique Esther Scroll was illustrated in the mid-1980s at Kibbutz Beit HaShita, a place that became a hub for Jewish-Zionist-humanist cultural renewal thanks to one remarkable man: Aryeh Ben-Gurion (yes, he was related to Israel’s first Prime Minister—his nephew, to be exact). Aryeh’s life’s work was the collection and documentation of the development of Hebrew culture. What began in a small hut in the 1950s eventually evolved, with the help of his colleagues, into “The Shitim Institute – The Jewish and Israeli Holiday Cultural Archive,” which is still based in the kibbutz to this day.

“The primary goal was always to bring the holidays closer to children and youth. That was the most important thing—to invest everything in the younger generation,” recalls Haggai Ben-Gurion, Aryeh’s son.

And he succeeded.

The illustrated Megillat Esther is a beautiful example of this vision.

Throughout his career as an educator and cultural leader, Aryeh Ben-Gurion served as a teacher, school principal, chair of the cultural committee of the kibbutz movement, and an educational emissary to Jewish communities in the United States. His deep commitment to Jewish heritage, his passion for reconnecting Judaism with the land after 2,000 years of exile—these values shaped his life. “The holidays were dear to him from as early as the 1940s, and he devoted his entire life to them. As proof—just look at what he named his firstborn son,” Haggai remarks with a smile (Hag, or Chag, means “festival” or “holiday” in Hebrew, haggai means “my festivals”).

Aryeh Ben-Gurion published dozens of holiday anthologies and produced editions of all five Megillot in Jewish tradition. However, for Megillat Esther, he envisioned something different—something that people would want to display in their homes rather than just another book on the shelf. He came up with an innovative idea: he approached the teachers at the Beit HaShita school and asked for their help—could they, as part of the curriculum, have the fourth- and fifth-grade students illustrate the Purim story?

The teachers welcomed the idea, and with the guidance of the art teacher, Tamar Carmi, the children created a collection of drawings to accompany the Megillah.

“When the illustrations were completed, he gathered them and took them with him to the U.S., where he had extensive connections within the Jewish community,” his son recounts. “There, he met Eric Ray, a Judaica expert mentioned at the end of the megillah, who connected him with a scribe who transcribed the entire megillah in the traditional Karaite script.” This unique fusion of an ancient text with children’s colorful illustrations created a meaningful link between Israeli children and Jewish communities abroad.

In Israel, the Megillah carried even greater significance—it became another expression of the way holidays were celebrated in the kibbutzim. Every class at the Beit HaShita school received a copy of the fully kosher Megillah, adorned with the children’s artwork. Ben-Gurion also distributed copies to cultural coordinators from different kibbutzim with whom he worked as part of his role. “For years, he kept the original drawings, each labeled with the names of the children who created them,” his son recalls.

One of those children, Tzur Adar, now a resident of the kibbutz once more, can still identify his own illustrations in the Megillah. “As far as I know, children from three consecutive school years contributed to the project. Art was always highly valued in our school—we had an entire section dedicated to creativity called Beit Omanuyot (House of Arts), with large tables and a kiln for firing clay.” Adar cherishes the Megillah and keeps a copy in his home. “Aryeh was a well-known and beloved figure in the kibbutz,” he reminisces. “By the time I was in elementary school, he was already an older man, but he would occasionally visit us before holidays to teach a lesson, and it was always fun and fascinating.”

Hemda Shefer, one of the kibbutz school’s teachers, also fondly remembers the project: “I had a good relationship with Aryeh Ben-Gurion, and he found it easy to approach me. The children were thrilled—it was a great honor for them. For years afterward, I kept the Megillah in my classroom, and every year before Purim, I would bring it out and read from it. To this day, it holds a place of honor in my home.”

The idea of illustrating the Megillah became well-known among educators, inspiring some to use it as a way to connect children with the holiday’s text and themes, even if their versions were never officially published. Ohad Sofer, head of the Music Department and Sound Archive at the National Library and a native of Kibbutz Beit HaShita, found at home a similar Megillah he had illustrated himself, likely at the age of six in kindergarten.

Aryeh Ben-Gurion had a remarkable ability to make holidays engaging for children (and adults alike). This Megillah stands as a beautiful reminder that each of us can adopt something from the annual cycle of Jewish festivals and make the holidays our own.

Acknowledgments – We extend our gratitude to past and present members of Kibbutz Beit HaShita who contributed to this article and to David Geffen, who donated an additional copy of the illustrated Megillah to the National Library, thus bringing its story to light once more.