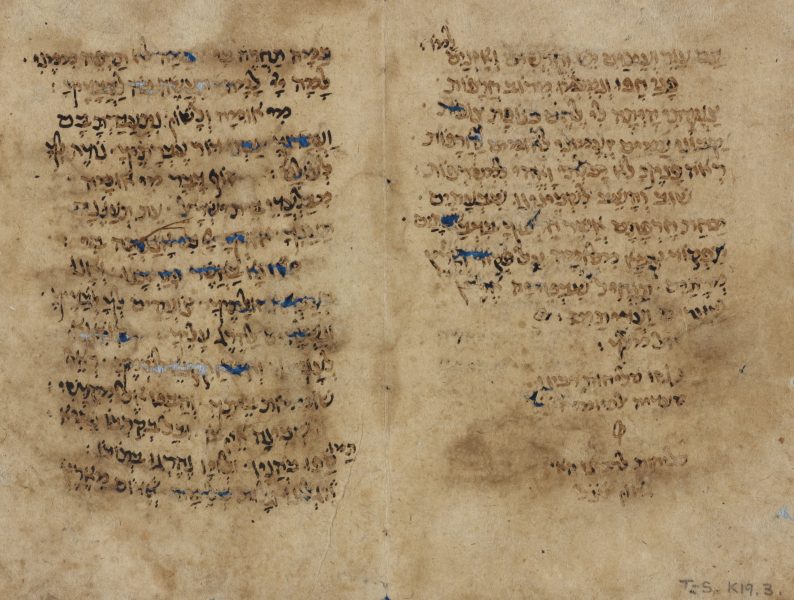

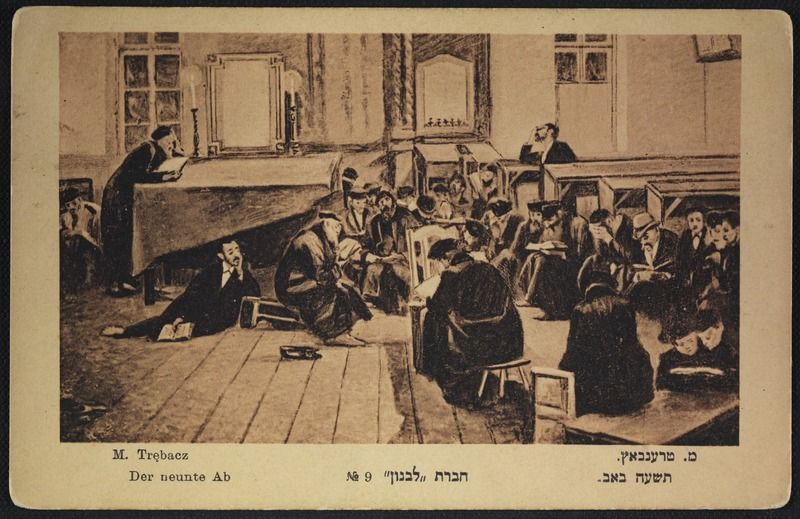

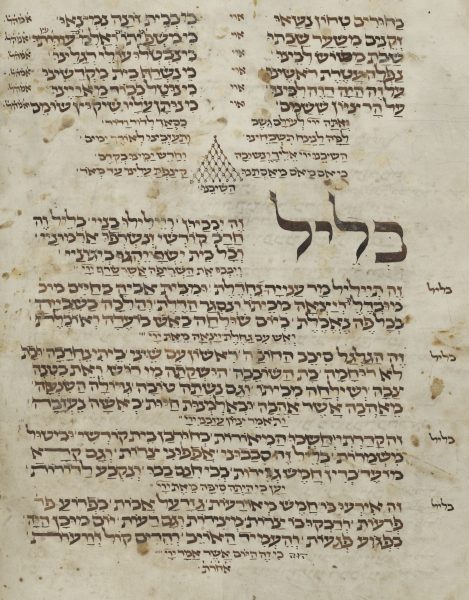

In synagogues across the world, congregants will gather this Saturday night and Sunday (August 2–3) to commemorate Tisha B’Av, the somber anniversary of the destruction of the holy temples in Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. and 70 C.E. The holiday, whose name means simply the ninth day of the month of Av, stands out for its mournful mood, a 25-hour fast and the recitation of both the Book of Lamentations and kinnot, poetic elegies that bemoan the temples’ destruction and Jews’ historical sufferings after being exiled from Israel.

But some synagogues in recent years have bolstered their offerings to make the holiday’s experience more meaningful. Along with the prayer services and the special Torah and haftarah readings tied to the day, classes are being held about calamities throughout Jewish history and the meaning of Tisha B’Av and its prayers.

That’s been the case for three decades in a Baltimore, Maryland, synagogue, where a local rabbi and history professor, David Katz, delivers a Tisha B’Av lecture on the meaning of some of the kinnot, which are notoriously difficult to comprehend. Another American rabbi, Yirmiyahu Kaganoff, now lives in Jerusalem, where each Tisha B’Av he leads a nearly four-hour class on selected kinnot for an audience of predominantly English-speaking immigrants. It’s an approach he hit on while serving as a congregational rabbi in Buffalo, New York, in the 1980s.

“Instead of droning on the kinnos, I took a selection of them and explained them,” said Kaganoff. “I want people to identify with what we’re doing here and, rather than droning, to make it a meaningful experience.”

For many Jews, Hamas’s attack on October 7, 2023, added new significance and meaning to an already somber date in the Hebrew calendar.

“October 7 changed the world. There was no other topic to be discussed. This was the greatest tragedy to befall the Jewish people in [recent] times,” said Jamie Geller, chief marketing officer for Aish, a worldwide Jewish-outreach organization that has produced films about the impact of the massacre over the past two years, screening them on Tisha B’Av. “This was the most relevant, timely, emotionally poignant connection to the tragedy,” she added.

Zev Eleff, the president of Gratz College, a Jewish institution near Philadelphia, said he’s noticed the trend to inject greater meaning into the holiday.

“Tisha B’Av has always been a day we mark with grief and introspection,” he said. “It’s never just for prayers, but also memory-marking.”

Jonathan Sarna, a historian of American Jewry, credits summer camps devoted to tradition with playing a key role in transforming Tisha B’Av and earning it a more prominent position on the calendar.

That started in about the 1940s when some camps in the United States seized on the vacuum between school terms to provide educational programming, he said.

Because some campers would be fasting, the administrators “wanted to distract their attention” with compelling material, he said. The experience, in turn, would develop some counselors and campers as future educators, he said.

“It was just natural for them to magnify Tisha B’Av, and they [later] brought those programs into synagogues and community centers,” said Sarna, who recently retired as a professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University.

Rabbis Kaganoff and Katz explained that their modified approach arose from grasping people’s search for deeper connection to the day. Of the approximately 60 kinnot (numbers are imprecise due to variations between the Sephardi and Ashkenazi communities and even between congregations), each rabbi focuses on fewer than 20 to discuss in their presentations — what Katz called “explications.”

Katz tends to select the same kinnot for discussion from year to year, while Kaganoff varies his offerings. Katz said his presentations always include four kinnot written by survivors of the Crusades, because, while uncomfortably vivid, they are authentic rather than flowery.

Katz recalled a time when kinnot had not been composed to mourn victims of the Shoah. That’s no longer the case, and Shoah-themed kinnot are commonly recited these days. Similarly, he said, “I’m sure, over the course of time, October 7 will enter the liturgy in one way or another.”

Kaganoff, who’s lived in Israel since 1997, noticed years ago “a movement for people to understand all of their prayers,” he said.

“The kinnot are very difficult. I have to explain each word as an allusion to a concept or an event or an idea,” he said.

“People want a full experience of davening [praying]. They want a full experience of talking to God. They want to know what they’re saying, rather than have a boring time. … They’re not interested in a rote religion. It’s a very good sign.”

Writer-editor Hillel Kuttler can be reached at [email protected].