Education for Jewish girls in Eastern Europe in the years before World War I was largely neglected. On one hand, we might picture a grandmother who knew how to pray and read from the Tzena U’rena on Shabbat. On the other hand, there are descriptions of illiterate women who sat in synagogue and followed the prayers only with the help of another woman guiding them through it.

The status and education of Jewish women were closely tied to social structure. Religious restrictions played a role, but no less significant were severe state limitations – particularly in Russia. As noted by historian Avraham Greenbaum, whose archive is preserved in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, the authorities took a strict stance on the opening of cheders (traditional Jewish schools or classrooms) for girls.

Even when the law allowed the establishment of boys’ cheders for a fee of three rubles per year, Tsarist officials adopted a particularly conservative interpretation. According to their reading of the law, only male teachers were allowed to open a cheder, and only for boys. In the rare cases when requests were submitted to open girls’ cheders, they were typically denied. In one memo, a Russian official wrote that he had relied on an interpretation of the Shulchan Aruch he received, possibly from a religious or converted Jew, from which he concluded that Jewish law explicitly forbade girls from learning.

And yet, cheders for girls did exist.

For example, Pauline Wengeroff wrote about such an institution where she herself studied. Author and educator Esther Rosenthal-Shneiderman described a cheder in her book Naftule Derakhim that was run by a woman in Czestochowa at the turn of the 20th century.

Sometimes, even when permitted, additional restrictions were imposed. In Poland, one of the few women granted a license to open a cheder for girls was Pessa Gutmacher. In letters she presented from a local rabbi, he vouched for her qualifications to “teach the Jewish language.” But unlike her male counterparts, her official license did not authorize her to teach “the Jewish religion.” Moreover, the license required her to teach Russian and limited enrollment to no more than 24 pupils.

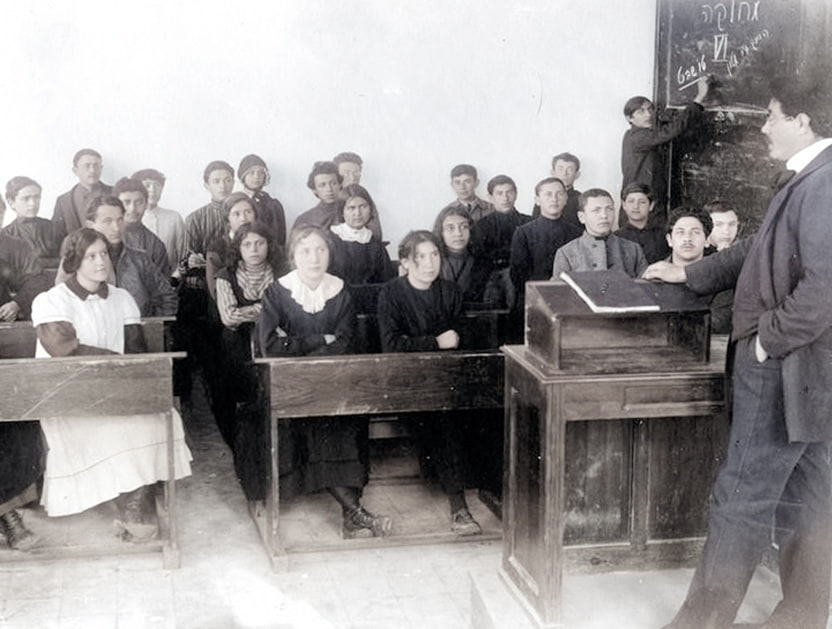

Surprisingly, while there were barriers to opening cheders for girls, the authorities were somewhat less stringent when girls attended cheders for boys. This led to the curious phenomenon of girls studying in boys’ cheders. Actress Bessie Thomashefsky recounted that as a child she was carried on the shoulders of a teacher’s assistant to the cheder. Eva Broido, who would later become a communist revolutionary, wrote in her autobiography that she left the cheder due to the boys’ intolerable behavior.

Chaya Weizmann (sister of Israel’s first president) studied Chumash and Hebrew in a boys’ cheder. Similar stories were told by Esther Schechter from Łomża, Poland. A document found by the late Professor Greenbaum, now digitized in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, describes the closure of a cheder after it was discovered that girls were studying there. According to the document, the teacher, Shia Fechter, pleaded for compassion, explaining that he was poor and elderly and unaware of any prohibition. He added that he had taught the boys and girls at separate times. Unfortunately, the document does not reveal what became of the cheder or its teacher.

So what kind of cheder was it?

In 1942, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research announced a contest inviting American Jews to submit autobiographies on the theme “Why I Left Europe and What I Achieved in America.” A total of 221 autobiographies were submitted, 174 by men and just 47 by women. Among other topics, the organizers asked participants to describe their education. The women described various learning environments – studying at home, with private tutors, or as apprentices. Four of them – Mary Weissman, Miriam Rosen, Rose Bayla, and Rose Sonnenfeld – wrote that they had studied in a cheder. None of them described the experience as unusual, and none specified whether the cheder had been for boys or girls.

It’s difficult to determine whether most Jewish girls in Eastern Europe before World War I received any form of structured education – and if so, what kind. Were they home-schooled? Were they taught by private tutors? Were most simply left illiterate? And those who were allowed into cheders – did they attend boys’ cheders that quietly included girls? Or was there perhaps a hidden network of informal “women’s cheders” operating in the background?

We will likely never know the full picture. Yet these testimonies reflect not only the complexity of educational life for Jewish girls in that era, but also the determination of these young women. Despite social prohibitions, legal obstacles, and practical challenges, there were parents committed to educating their daughters, and girls who found ways to study, to read, and to understand.

Even when doors were closed, girls found ways to learn, to know, and to connect to the world of Torah and Jewish culture. In secrecy, in the shadows, or at the margins of society – another chapter was written in Jewish history: a chapter of curiosity, of yearning, and of women’s persistent defiance in the face of time and tradition.

Further Reading:

Adler, Eliyan R., In Her Hands: The Education of Jewish Girls in Tsarist Russia, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2011

Greenbaum, Avraham, “The Girl’s Heder and the Girls in the Boys’ Heder in Eastern Europe before World War I.” East/West Education, 18, 1. (1997): 55-62