“I have a very important item which I must give to you,” said the voice on the other end of the telephone, “And I ask that you come to collect it personally, as soon as possible.” The name of the man who telephoned the archive department some six months ago is a familiar one in the Library: the engineer Yosef Weichert, son of Michael Weichert whose large, extensive archive has been preserved in the National Library for almost fifty years.

A surprise awaited us when we came to visit him in Tel Aviv: Mr. Weichert gave us an item which for various reasons had not been deposited with the rest of his father’s archive material, and had remained in the family’s possession. With great excitement he handed us an album with a faded cover and said: “The time has come to present you with this historical item. It is important that the world become aware of the story and remember and know that the Poles collaborated with the Germans’ cruel actions during the Holocaust and were fully aware of the horrors.”

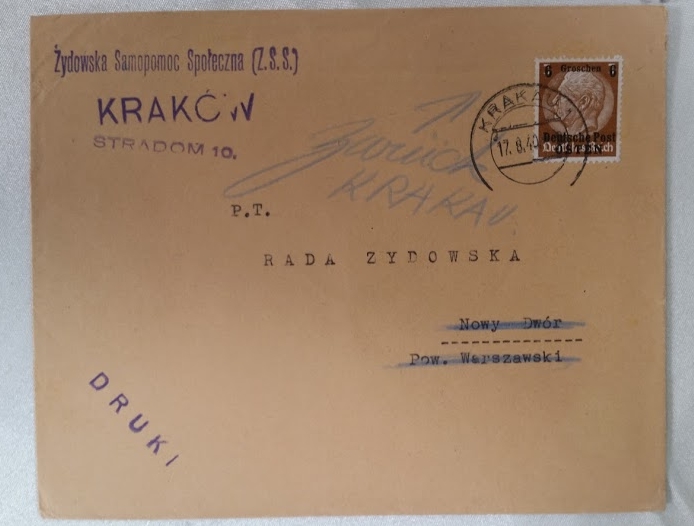

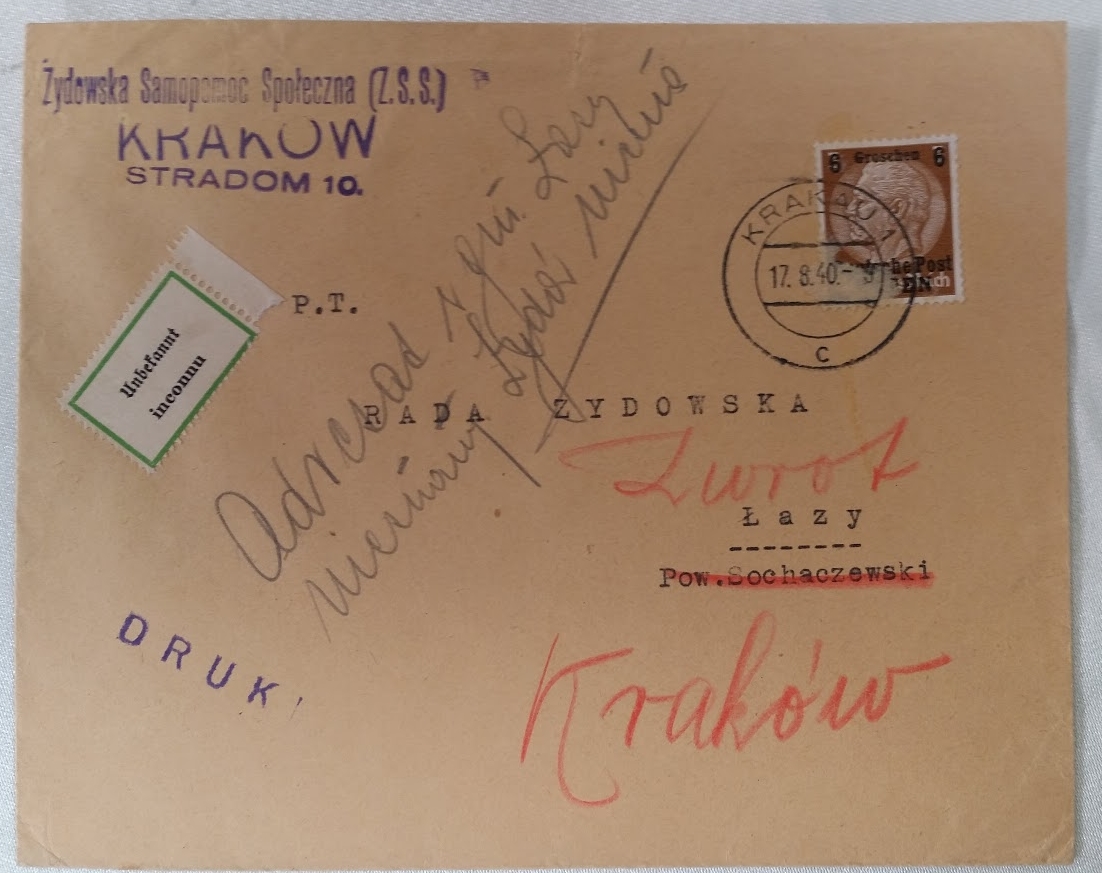

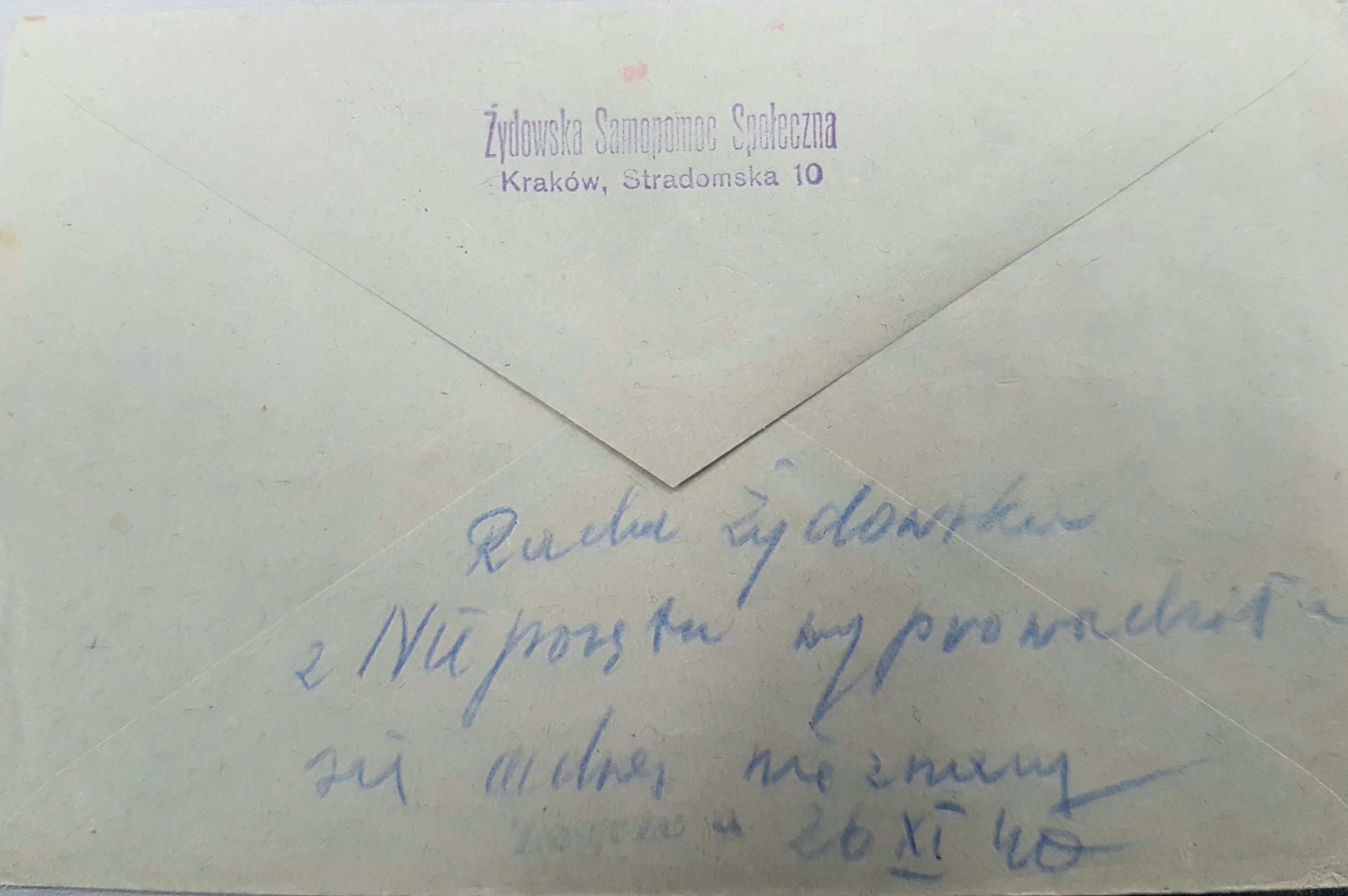

Meticulously arranged in the album were 59 letter envelopes sent between September 1940 and May 1941 to the various branches of the Jewish Social Self-Help Organization (ZSS) from the central office in Krakow. All the letters sent by the chairman of the organization, Michael Weichert, were returned to him.

The Polish postal service returned them to his office, a while after they were sent, with various handwritten additions on the envelope: “Left the address”; “The Jews were deported” or “The Jewish council no longer exists”.

Without a doubt, the Polish postmen were fully aware of what had befallen the addressees whose letters were returned to the sender. Michael Weichert was horrified by the returned mail, knowing that each envelope bearing a Polish postman’s comment hinted to a community which no longer existed. In his eyes, the envelopes, some of which were also stamped with a Polish stamp: “Victory to the Germans on all fronts!” were also an expression of the collaboration and unrestrained affinity many Poles felt toward the Nazi’s actions.

Weichert decided to conceal the envelopes in a hiding place, together with other documentation from that time. After the war, he removed the envelopes from their hiding place, so his son who witnessed his actions told us, and added them to his archive. But who was Michael Weichert and what was the organization for which he sent these letters to dozens of communities throughout Poland?

Michael Weichert was born in 1890 in the city of Podhajce, Eastern Galicia. His natural affinity for the world of literature and theatre and his excellence in classical studies mapped this talented young man’s path, and he decided to dedicate his life to Jewish theatre.

After completing his studies, with excellence, in the law faculty of Vienna University, he travelled to Berlin and registered for studies at the Academy of Theatre Arts headed by the well-known director Max Reinhardt. When the First World War came to an end Weichert returned to Poland and settled in Warsaw, where in 1929 he opened a studio for young experimental theater which gradually developed into the “Young Jewish Theatre”. Despite Weichert’s great success as director of the theatre, he needed another job to supplement his meager income, and he worked in his profession as an attorney in the service of various Jewish charitable and social aid institutions.

When the Second World War broke out, Weichert found himself in the eye of the storm – he was the legal consultant of the umbrella organization which unified the Jewish self-help social aid organizations in Poland. His natural leadership abilities led to him being the person who decided to accept the Germans’ offer to continue to operate these organizations. The aid funds sent to the organization from the Joint Distribution Committee in America were the deciding factor in the Germans’ decision to permit the activity to continue, under their tight supervision. In May 1940 Weichert was transferred to Krakow, where he was appointed as chairman of the Jewish Social Self-Help Organization (in Polish: Zydowska Samopomoc Spoleczna – ZSS).

Weichert was joined by Marek Biberstein, the head of the Krakow Judenrat as co-director of the organization. Many people were disconcerted by the organization’s close connections with the German authorities, and an attempt was even made at the end of the War to accuse Weichert of collaboration with the Nazis. Weichert was deeply hurt by these accusations, and spent many years clearing his name and proving his innocence.

All of the ZSS’s foreign relations had to be conducted – by order of the authorities – through the German Red Cross, and the organization was under close supervision of the authorities. Even its management was approved directly by the authorities in September 1940. The organization had advisers for each of the four Generalgouvernement districts, as well as representatives on local aid committees. The ZSS distributed food to the Jews of the Generalgouvernement and directed other widespread aid activities – such as operation of centers for agricultural training for the members of the socialist youth movements, aid to Jews in the forced labor camps, and more.

Many towns had branches of the organization which were all subordinate to Weichert’s management. The management of the organization in Krakow, headed by Weichert, coordinated, initiated and supervised the social aid activities in all the towns under its authority, including of various organizations which were effectively subservient to it but were often given full freedom of action. During the three years of its activity, this organization dealt with some half a million people, half of the total number of Jews in the area it was responsible for. Despite the tremendous disparity between the needs of the public and the ability to help them, the self-help organization managed to provide portions of food to the soup kitchens, as well as to send packages of dry food, medicine and clothing to the poor. The Germans ordered the organization to shut down once they began the implementation of the ‘Final Solution’. Its activity ceased on July 29, 1942, and a Jewish self-help office was opened in its stead, which was subordinate to the Gestapo and closely supervised by it.

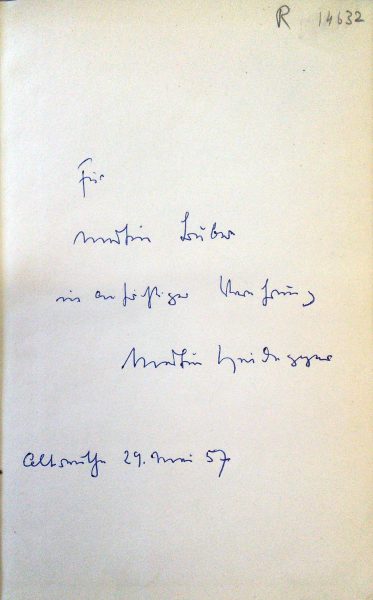

The many frictions between Weichert and the various Polish underground movements led to him being forced to hide from them and to his life being in two-fold danger – not only from the fury of those who saw him as a Nazi collaborator, but also due to having been sentenced to death by the Germans themselves, who issued an arrest order against him. Weichert, managed to survive the Holocaust, along with his wife and son. They arrived in Israel in 1958, bringing with them a large and valuable archive of documentation which has unique significance for the history of the Holocaust, as well as, and perhaps primarily in Weichert’s eyes, material which told the story of the Jewish theatre in pre-Holocaust Poland, during the War and in the short-lived period of flourishing after the War.

The envelopes of the letters sent back to Weichert from the various branches of the aid organization he managed are important testimony and a painful memory of those difficult days. It was the Polish postmen who informed him about the destruction of dozens of Jewish communities throughout Poland. This extraordinary documentation is now preserved in the National Library and is available to researchers and historians who undoubtedly, will continue to study this dark and terrible period of human history.