When Audrey Ades reads aloud from the children’s book she wrote in 2020, Judah Touro Didn’t Want to be Famous, she is struck at the gatherings by the varied reactions of two groups in attendance.

Adults are impressed by the generous charitable contributions made by Touro, an American Jew who died in 1854. Children wonder why Touro avoided the limelight he’d earned for doing such good deeds.

The kids “did not understand why a person would not want to be famous, which was fascinating to me,” said Ades, a resident of Florida. “They were really grappling with that. I think they were more interested in that than the philanthropy.”

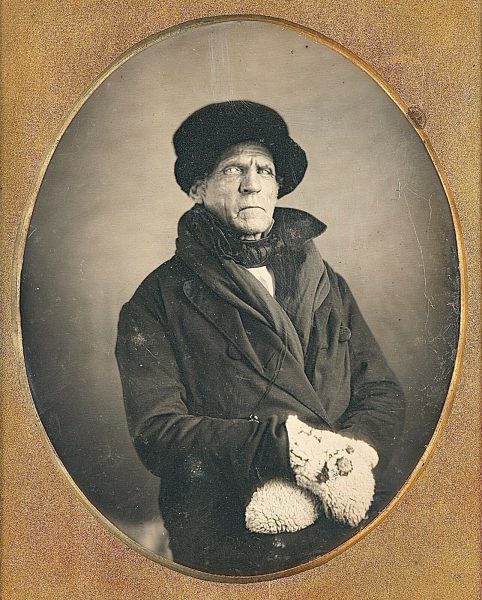

A prosperous merchant, Touro made donations and bequests to purchase buildings for churches and synagogues, to acquire property for cemeteries and to construct hospitals. Most of the funding went to places in New Orleans, the city where Touro lived most of his life, but also to New York and New England.

The acts had in common their occurring anonymously, often as a condition of the funding. Much of Touro’s charitable contributions became known publicly only after his death. He disposed of most records during his lifetime.

He “embodies humility and success,” said Alan Kadish, the president of Touro University, founded in 1971.

Touro was a “rags-to-riches” story, as a self-made man who gave approximately $500,000 to charity, the equivalent of $12 million today, and whose will was “the most generous” in America up to then, historian Jonathan Sarna said in an online video address to the university in 2021.

A “turning point” in Touro’s life, Sarna said, was a year-long recovery from serious injuries sustained in the Battle of New Orleans, during the War of 1812. As he recuperated, Touro turned inward and became “eccentric and reclusive.”

In her notes appearing at the end of the book, Ades speculated that Touro’s father, Isaac, taught his children about the rungs of charity conceived by the great Jewish thinker Maimonides (Rambam), of which remaining anonymous is the most noble.

“By donating in secret, Judah reached the highest levels of charitable giving in Jewish tradition,” she wrote.

June 16, 2025, marked 250 years since Touro’s birth in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1775, but Ades did not know of the milestone date’s approach. Kadish, the university president, said his institution was not planning any events to mark the semiquincentennial. Those working at Touro, a restaurant in Jerusalem’s posh Mishkenot Sha’ananim neighborhood, were also oblivious. The eatery is located a few blocks from Tura Street, named for Touro but misspelled in English. The construction of Mishkenot Sha’ananim, the first Jerusalem neighborhood built outside the Old City walls, was funded by Touro’s estate a few years after his death.

The notable birthday’s passage with little to no fanfare is probably as Touro would have wanted it. Even Newport’s famous Touro Synagogue was formed and endowed not by Judah, but by his brother Abraham. Opened in 1763, it is the oldest synagogue in the United States. It continues to function as a house of worship and is a designated historic site run by the National Park Service. The synagogue is best known as the repository of a letter written by President George Washington (who visited the synagogue in 1790), expressing the U.S. government’s commitment to religious freedom. “[T]o bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance,” Washington’s letter legendarily affirms.

Isaac Touro had died by then, but he’d have understood the power of Washington’s words. He was born in Amsterdam to descendants of Jews who had escaped the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions.

A foundation that preserves the Newport synagogue’s history counts Keith Stokes, a relative of the Touros, as a board member. Serving in that role “is who I am,” said Stokes, recently appointed as Rhode Island’s historian laureate.

Stokes remembers his grandmother, Bessie Forrester Barclay, who by then had converted from Judaism to Episcopalianism, taking him to Newport’s Redwood Library and telling him stories of Isaac Touro’s arrival in the United States and “that the Jewish ancestors were part of the great families of Spain.”

Judah Touro remains known today partly through the synagogue; the university, which this year has 19,000 students attending its colleges and medical schools in the American states of New York (where it is headquartered), Nevada, Illinois and California, and in Israel, Russia and Germany; as well as the hospitals he founded or left massive bequests to: Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital (which Abraham Touro established), New Orleans’s Touro Infirmary and New York City’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

“He was a role model of generosity of money and philanthropy to Jew and Christian alike. It’s really only after Judah Touro passes away that we see so many things named for him,” said Sarna. Touro’s philanthropy and frugal living were “like [that of] Warren Buffet,” Sarna said.

“Judah Touro becomes one of the best known and most respected Jews, known to Jew and non-Jew for his philanthropy and for the many things his money was able to accomplish.”

Writer-editor Hillel Kuttler can be reached at [email protected].