One of the world’s oldest known Esther scrolls (also known as a “megillah“) has been gifted to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, home to the world’s largest collection of textual Judaica, where it has also been made available online for the first time.

Esther scrolls contain the story of the Book of Esther in Hebrew and are traditionally read in Jewish communities across the globe on the festival of Purim, which will take place on February 25-28 this year.

Scholars have determined that the newly received Esther scroll was written by a scribe on the Iberian Peninsula around 1465, prior to the Spanish and Portuguese Expulsions at the end of the fifteenth century. These conclusions are based on both stylistic and scientific evidence, including Carbon-14 dating.

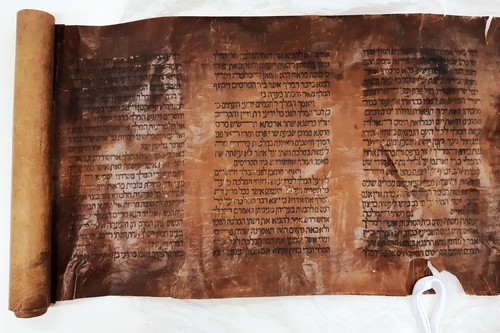

The megillah is written in brown ink on leather in an elegant, characteristic Sephardic script, which resembles that of a Torah scroll. The first panel, before the text of the Book of Esther, includes the traditional blessings recited before and after the reading of the megillah, and attests to the ritual use of this scroll in a pre-Expulsion Iberian Jewish community.

According to experts, there are very few extant Esther scrolls from the medieval period in general, and from the fifteenth century, in particular. Torah scrolls and Esther scrolls from pre-Expulsion Spain and Portugal are even rarer, with only a small handful known to exist.

Prior to the donation, this scroll was the only complete fifteenth century megillah in private hands.

The medieval scroll is a gift from Michael Jesselson and family, continuing long-standing family support of the National Library of Israel and its collections. Michael’s father, Ludwig Jesselson, was the founding chair of the International Council of the Library (then known as the “Jewish National and University Library”) and a strong leader and advocate of the Library for decades.

According to Dr. Yoel Finkelman, curator of the National Library of Israel’s Haim and Hanna Salomon Judaica Collection, the new addition is “an incredibly rare testament to the rich material culture of the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula. It is one of the earliest extant Esther Scrolls, and one of the few 15th century megillot in the world. The Library is privileged to house this treasure and to preserve the legacy of pre-Expulsion Iberian Jewry for the Jewish people and the world.”