Station One: Cairo, 1943 – Love and Zionism

He was a young British Jewish intelligence officer, responsible for maintaining contact between the Jewish Agency and British forces in Egypt. She was the second daughter of a senior Jewish engineer employed by the Suez Canal Company. The encounter took place in the sweltering heat of Cairo in 1943.

Both were far from the places where they were born and raised, while a world war raged around them and threatened everything they knew. Even so, the two exchanged shy yet persistent glances.

Aubrey Solomon Meir Eban was born in South Africa. His full name, which he seldom used, reflected the presence of two fathers in his life: his biological father, who died of cancer when Aubrey was still a toddler, and his stepfather, who formally joined the family when Aubrey was six and with whom he never truly got along.

Eban received an outstanding British education at some of the United Kingdom’s most prestigious institutions. At the same time, he grew up in a home where Judaism and Zionism were the guiding lights. These two sides of his identity were already visible during his university years: He studied at Cambridge, a world-renowned symbol of British excellence and learning, and even served as president of the student union, yet he specialized in Semitic languages, was active in the Zionist youth movement, and contributed numerous articles to its journal.

When the Second World War broke out, he was drafted into the British army. In 1943 Eban was posted to Cairo in a position that was political by nature, serving as liaison between British forces in Egypt and the Jewish Agency and everything it represented. It was an early step toward the distinguished diplomatic career ahead of him.

Suzy Ambache was born in Ismailia, a European enclave in Egypt where employees of the Suez Canal Company lived in something of a secluded bubble. Her family’s sentiments, however, lay to the northeast, in the Land of Israel. At home they spoke only Hebrew, and Suzy learned French only when she had to enter school.

The two first met at an afternoon tea session at the Ambache home, to which the young British officer, an outsider, had been invited. At first, he seemed to take little notice of the daughters of the family. But then, Suzy later recalled, “suddenly, at some moment, Aubrey glanced at me; he just looked. I still remember that look. I knew that glance expressed a sense of special attention.” It was the beginning of a determined and enthusiastic courtship, during which Suzy received many passionate, eloquent, and carefully written letters.

Before the war even ended, in March 1945, this young couple, who had come from such different cultures yet shared the same dream of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, were married.

They created a home of their own.

And when they immigrated to Israel, “Eban” became “Even” – Hebrew for “stone”.

Station Two: New York, 1947–1959 – The Voice of a Newly Born State

Barely a year after their wedding, Abba Eban was summoned back to London. He joined the political department of the Jewish Agency, working closely with two other senior Jewish diplomats: Chaim Weizmann and Moshe Sharett. All their time and energy were devoted to one issue: the approaching United Nations vote on the partition plan.

The situation looked bleak. British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin had declared that “there is no prospect of resolving this conflict by any settlement negotiated between the parties,” and his close adviser told the Jewish delegation, “Don’t you know that the only way a Jewish state will be established is if the U.S. and Soviet Union agree? Nothing like that ever happened. It cannot possibly happen. It will never happen.”

But diplomacy is not for the faint-hearted or those who lack faith. Traveling constantly between London and the United Nations headquarters in New York, Eban did not rest for a moment. He worked publicly and behind the scenes, using his eloquence and rich language to appeal directly to emotion.

In the end, thirty-three nations voted in favor of the UN partition resolution, and the State of Israel was born.

Eban, then only thirty-five, was appointed Israel’s ambassador to the UN, and shortly afterward also ambassador to the United States. These two central positions made him, in David Ben-Gurion’s words, “the voice of Israel.” He now stood at the most important podium in the world at the most critical of moments. Would the newly established state receive the support of the world’s great power? What form would that support take, and how would the United Nations treat this new country?

This was the task Eban took upon himself: to shape Israel’s image and its relations in the international arena. He carried out this role with a combination of elegance, intelligence, and determination that few could resist.

Although Israeli at heart, he appeared as far as possible from the stereotypical Israeli. He was impeccably polite, even when he had harsh things to say, and his English was so polished that it surpassed that of representatives from native English-speaking countries.

“When he delivered a speech,” his nephew, President Isaac Herzog, later recalled, “the American delegation would take dictionaries out of their pockets.”

Eban did not always agree with the decisions of Israel’s leadership or its actions, but he was the one who had to present them to the world, even when he himself remained unconvinced. He became an expert at doing so.

On one occasion, when a particular Israeli military action came before the UN Security Council, he rose as usual to defend Israel’s position, even though he personally believed (and told those close to him) that a different course of action had been possible.

Years later, Ben-Gurion told him about that speech: “My dear Eban, until I heard your address at the UN, I was not at all convinced there was justification for the army’s action. After hearing your words, I am now convinced beyond any doubt.”

Station Three: Rehovot, 1959 – A Dream of a Different World

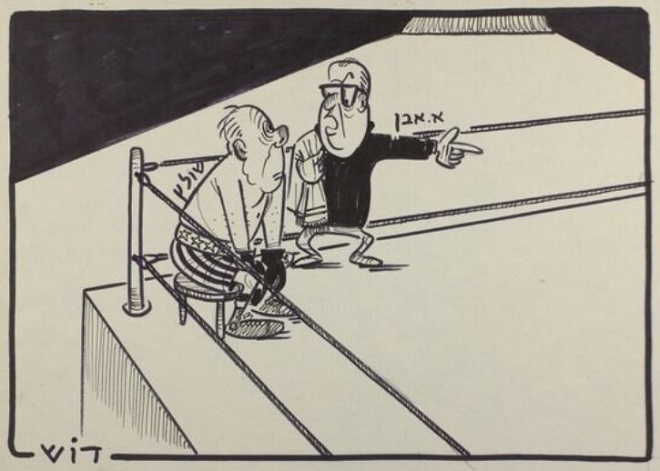

In the summer of 1959, the Eban family returned to Israel. By that time Abba Eban was a respected and admired figure across the world, with countless achievements on behalf of the State of Israel. But his British manners did not serve him well in Israel’s rough political arena, and in the years that followed he struggled to find his place.

On paper he obtained coveted positions. He was elected to the Knesset and served as Minister of Education and later as Deputy Prime Minister. Yet none of these roles truly excited him, and in none of them was he able to make full use of his remarkable abilities, talents, and international connections.

He did, however, hold one position that brough him satisfaction: President of the Weizmann Institute of Science.

In that role, he convened the “International Conference for the Advancement of the Emerging Countries through Science” in the summer of 1960, known more simply in Hebrew as the Rehovot Conference.

For most Israelis, the event passed with little media attention, aside from the arrival of numerous distinguished but somewhat exotic guests such as the prime minister of Nepal, the president of the Republic of the Congo, and deputy prime ministers from Africa and Asia. Leading scientists from around the world also took part.

The aim of the conference was to explore scientific and technological means to advance and develop the newly independent states that had emerged following the global reshaping of borders in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s.

The conference was close to Eban’s heart. He believed deeply in the power of international cooperation. He worked tirelessly to bring notable figures to the event, both from abroad and from within Israel. He very much hoped that Jewish and Israeli thinkers and leaders would take part. The National Library preserves extensive correspondence between him and Martin Buber, reflecting Eban’s efforts to persuade Buber to attend the conference, then to speak at it, and finally to endorse its conclusions.

Much like Eban himself, it seems the significance of the conference was recognized much more readily outside of Israel than in the country itself. Its conclusions were circulated as an official UN document, and ideas raised during the conference became the basis for numerous collaborative ventures between countries. In Israel, however, the Rehovot Conference never entered the roster of formative national events, and few recall it as one of Eban’s achievements.

Station Four: Jerusalem, 1966 – A Foreign Minister at War

In 1966 Eban finally received the role that seemed made for him. He was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, first under Levi Eshkol and later under Golda Meir.

This was an extraordinarily difficult period for Israel in the international arena. Only a year into his tenure, he once again stood at the UN podium defending Israel’s actions in a war it had just fought against the combined armies of its Arab neighbors, a war over its very survival and one in which Israel had achieved a decisive victory.

“This is the first war in history,” he declared before the often hostile members of the UN Security Council, “which has ended with the victors suing for peace and the vanquished calling for unconditional surrender.”

Eban believed in peace, yet he also believed in Israel’s obligation to safeguard its achievements and in its right to a defensible territory that did not amount to “Auschwitz borders,” as he himself described it,

When Egypt approached the UN accusing “stubborn” Israel of remaining in the territories it had captured, it was Eban who succeeded in inserting Israel’s position into one of the UN’s most significant resolutions, Resolution 242, which established the principle of withdrawal only in exchange for peace.

In the years that followed, he continued in the role that drew most deeply upon his abilities. In Israeli memory he came to embody the “eternal foreign minister,” as though no one had held the position before him and no one could possibly follow.

On Yom Kippur in 1973, his political secretary woke him up by nearly kicking his door down (Eban was a heavy sleeper), plunging him straight into the terrifying early hours of the war that broke out that fateful day.

But neither his international reputation nor his personal relationship with Henry Kissinger helped him at home. After Golda Meir resigned in the aftermath of the war, incoming prime minister Yitzhak Rabin offered Eban the post of Minister of Public Diplomacy. Eban considered the offer “humiliating,” and with that, a brilliant political and diplomatic career came to an end.

Station Five: Legacy

Even after leaving government, Eban did not withdraw from public life. He devoted his time and energy to continuing what he saw as his life’s mission, now on different stages. He became a sought-after lecturer and wrote numerous books in English. Abroad he was widely admired, named one of the ten best speakers in the world, and awarded multiple honorary doctorates from leading universities.

At seventy-five, none other than Henry Kissinger organized a birthday celebration for him at the UN building. The event drew the elite of American and international diplomacy, including Jacqueline Kennedy and the Egyptian ambassador. When a journalist remarked, “This is a rather unusual tribute at the UN, isn’t it?” Kissinger replied simply, “We are dealing with an unusual man.”

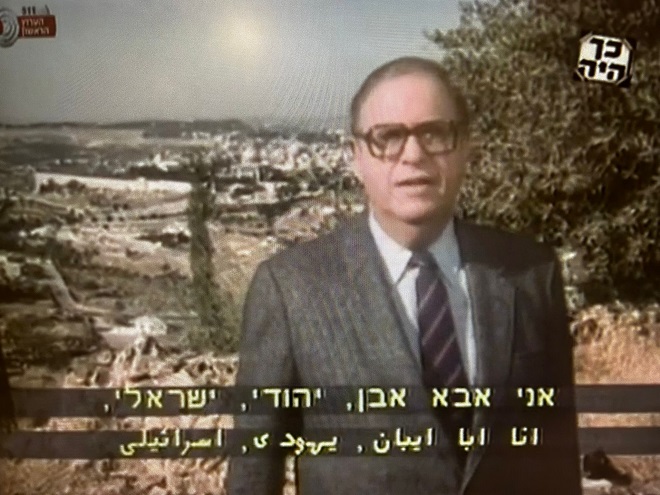

With decades of public service and personal achievement behind him, Eban turned to creating what he saw as one of his most important legacies: the television series Heritage: Civilization and the Jews.

The series sought to tell the story of the Jewish People to the world and, perhaps above all, to Jews themselves. It was first broadcast in Israel in the early 1980s and later in the United States. Long after its initial airing, it continued to serve as an educational tool for teaching Jewish history.

I am Abba Eban,” he proclaims in the opening monologue, a statement that perhaps more than anything else reflects how he viewed himself and the role he believed the Jewish People played in world history.

“A Jew, a citizen of Israel, educated in England, by training – a scholar of history and language; in recent decades – a diplomat and member of my country’s parliament. In the nine one-hour episodes of this series, we’re going to show you history through a microscope, focusing on the experience of a single small people – small in size and space and power. We tell their story, not just because of its constant drama, but because their ideas have played a central and influential role in human affairs, because their history is a link between our origins and our present. You cannot recount the story of civilization without coming face to face with what the Jews have thought, and felt, and written, and performed.”

In 2001 he was invited to receive the Israel Prize for Lifetime Achievement for “special contribution to society and the state.” By then he was ill, and his wife Suzy attended the ceremony to accept the award on his behalf.

Eban left an indelible mark on Jewish and Israeli history. He regarded diplomacy as a mission of the highest order. When others joked that diplomacy, “unlike a straight line, is the longest distance between two points,” he did not laugh. Instead, he responded with gravity, speaking of the profound significance of the State of Israel, which he loved and believed in despite everything. And even if no diplomat like him has arisen since, and even if some Israelis mocked his elevated English and his un-Israeli demeanor, he remained an inspiration to many who represented Israel on stages around the world.