“If it wasn’t for the nice Jewish people, we would have starved many a time. I will love the Jewish people, all of my life.”

(Louis Armstrong, Louis Armstrong: In His Own Words: Selected Writings, p. 9)

The year is 1907. In the sweltering summer heat of New Orleans, a seven-year-old boy is pushing a cart loaded with coal and scrap down a dusty street. The work is grueling – cleaning bottles, hauling coal – and demands that the child raise his young voice, shouting to attract customers as he pushes the heavy cart forward. In the evening, instead of heading home, he sits down to eat dinner with the family who have employed him and even taken him in, unofficially – the Karnofskys, poor Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. After the meal, the mother, Tillie, picks up baby David in her arms and sings Russian Lullaby, with the boy joining in.

Like many Jews at the turn of the 20th century, the Karnofsky family had fled the Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire (now Lithuania) and arrived in the United States penniless. They settled in one of New Orleans’ poorest neighborhoods, home mostly to African Americans. They opened a small business collecting and selling scrap throughout the city, and at night sold their haul from coal carts in the red-light district. To run the business, they bought two horses and wagons, and hired local children from poor families to work for them. (It wasn’t until 1936 that U.S. law prohibited the employment of children under 16.)

That young boy, who had no idea he would one day become one of the greatest jazz musicians of all time, was Louis Armstrong, or “Satchmo,” as he was fondly nicknamed. Years later, when he was already an international superstar, Armstrong received a gold Star of David pendant from his friends Abe and Francis Donen, who owned a jewelry shop in Los Angeles. To Armstrong, the pendant was a reminder of the time he spent with “my Jewish family,” as he called the Karnofskys, and of the poor boy he once was in New Orleans. He never took it off. That little boy, so in need of support and encouragement, found it in a poor Jewish immigrant family from Lithuania.

Louis Armstrong was born in August 1901 in New Orleans. His mother was a single parent who worked from morning to night to support him and his sister. At the age of seven, he began working for the Karnofsky family. That job altered the course of his life, making him a fixture in their home, and sparking a deep sense of kinship and love toward the Jewish People as a whole.

The work with the Karnofskys was not easy, as Armstrong would later recall. “The Karnofskys would start getting ready for work at five o’clock in the morning. And me, I was right there along with them,” he wrote. “I began to feel like I had a future and ‘It’s a Wonderful World‘ after all.

That sense of possibility wasn’t just thanks to the job and the wages. The Karnofskys became a kind of adoptive family. They nurtured his love of music, and perhaps more importantly, gave him the belief that he could become a musician.

They also helped him acquire his first instrument. One day, while riding through the French Quarter with Morris Karnofsky, the father, Louis spotted an old, rusty cornet in a shop window. It cost five dollars, a huge sum for a poor kid in New Orleans at the time. For Louis, it seemed like an impossible dream. But Morris saw the spark in his eyes and encouraged him to buy it. He gave Louis a two-dollar advance on his wages to help him get started. Over the following weeks, Louis saved fifty cents each week until he had enough to make the purchase. . “The little cornet was real dirty and had turned real black. Morris cleaned my little cornet with some brass polish and poured some insurance oil all through it, which sterilized the inside. He requested me to play a tune on it. Although I could not play a good tune Morris applauded me just the same, which made me feel very good.” Armstrong later recalled.

While selling scrap from the cart, Armstrong used a simple tin horn to call out to customers. One day, he removed the mouthpiece, opened and closed the horn’s bell with his fingers, and discovered he could make music. Children from the neighborhood would gather around him, and he’d give them private concerts. Admission was paid in empty bottles, which he later sold. “The kids loved the sounds of my tin horn,” he remembered, “After blowing into it a while I realized I could play ‘Home Sweet Home’ – then here come the Blues. From then on, I was […] tootin away.”

Armstrong’s trumpet playing wasn’t the only thing shaped by the Karnofskys, so was the deep vocal style he became known for. “When I reached the age of eleven I began to realize that it was the Jewish family who instilled in me singing from the heart. They encourage me to carry on,” he wrote.

With their support and encouragement, Armstrong began to believe in his chances of becoming a musician – “As a young boy coming up, the people whom I worked for were very much concerned about my future in music. They could see that I had music in my soul. They really wanted me to be something in life. And music was it. Appreciating my every effort.”

When Louis Armstrong Snacked on Matzot

More than once, Louis Armstrong stayed for dinner with the Karnofsky family – “My first Jewish meal was at the age of seven. I liked their Jewish food very much. Every time we would come in late on the little wagon […] when they would be having supper they would fix a plate of food for me, saying – you’ve worked, might as well eat here with us. It is too late, and by the time you get home, it will be way too late for your supper. I was glad because I fell in love with their food from those days until now.”

Armstrong’s love for Jewish food included a dish not generally regarded as a delicacy: matzah. Throughout his life, he regularly ate matzah, which became one of his favorite snacks, not just during Passover, but all year round. “My wife Lucille keeps them in her bread box so I can nibble on them any time that I want to eat late at night,” he once said.

Hello, Dolly. This is Louis, Dolly

Despite his deep connection with the Karnofsky family, Armstrong’s early life was far from easy. He dropped out of school at age eleven, and his teenage years were marked by hardship. At times, he, his mother, and sister were forced to share a tiny one-room apartment, sleeping together on a bed with no mattress. For a period, one of his mother’s partners was physically abusive toward him.

At fifteen, Armstrong attempted to join the bustling criminal underworld of New Orleans, working briefly as a pimp with a sex worker named Nootsy. Their relationship quickly turned sour and ended when she stabbed him in the shoulder. That was when Armstrong realized: The criminal lifestyle wasn’t for him.

Amidst the poverty and street violence, the streets of New Orleans pulsed with the earliest sounds of jazz – sounds that captivated Armstrong and lit the path toward his escape. In addition to working with the Karnofskys, he joined a street performance troupe. Around the age of sixteen, he left the family’s business after being hired by a band that played aboard a Mississippi River steamboat. The makeshift stage on the riverboat was far from glamorous, but it was there – on the water, performing for passengers – that he learned to read sheet music for the first time. He also honed his skills through nonstop playing and improvisation, adapting to the changing moods of the crowd.

Armstrong would later describe his years on that steamboat as “my university.”

From the riverboat, he moved on to Chicago, performing in jazz clubs across the city, before heading to New York. In the Big Apple, he transformed from a rising sideman into a trumpeter who had everyone talking.

In the years that followed, Armstrong founded the legendary ensembles Hot Five and Hot Seven, recording seminal jazz tracks like West End Blues and Potato Head Blues, and quickly became one of the most beloved musicians in the genre.

By the 1960s, he was acting in films, collaborating with Ella Fitzgerald, and, thanks to What a Wonderful World, climbing the music charts as a vocalist. Armstrong became one of the most famous and successful musicians in the world. His transformation from a penniless boy with a battered cornet playing on the streets of New Orleans into a global musical icon was complete.

A Jewish Lullaby and a Visit to Israel

Even after he left New Orleans, Armstrong never lost touch with his “Jewish family.” Every time he returned to the city, he visited the Karnofskys, and family members attended his shows wherever they could. He even recorded his own version of Russian Lullaby as a tribute, though his rendition followed the version popularized by Irving Berlin (written in the late 1920s).

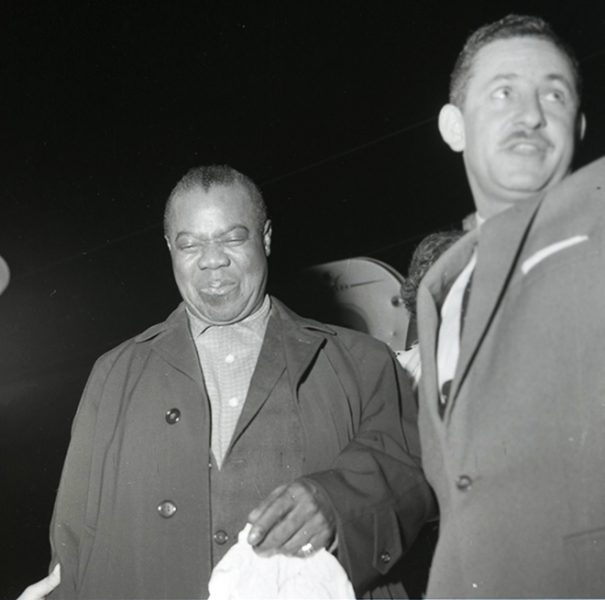

In 1959, whether because of his connection to the family or not, Armstrong came to perform in Israel.

Armstrong was welcomed at the airport by hundreds of fans, but his visit to Israel was also met with significant protest from the ultra-Orthodox community. One of his concerts was scheduled to take place in the town of Petah Tikva on a Friday night, prompting outrage over the decision to perform during Shabbat. On April 17, 1959, the HaTzofeh newspaper reported that the protest had escalated to the point where a telegram was sent directly to Armstrong in New York, where it was received by his wife, Lucille.

The rabbis of Petah Tikva also sent a telegram to the local impresario Dov Glickman (Goudik), who was organizing Armstrong’s performances in Israel, asking that the Friday night show be canceled. Goudik replied that Armstrong’s team had no objection to canceling the concert, as long as they still received the payment they had been promised. Since no payment was made, the rabbis of Petah Tikva launched a public campaign against the concert. Despite the protests, the show went ahead as scheduled.

Even though Armstrong was one of the world’s most celebrated jazz musicians, not all Israeli critics were impressed. A reviewer in Davar wrote that “his singing is not pleasing to the ear.”

Following his performances in Israel, Lebanon officially banned Armstrong from entering the country and declared he would not be allowed to perform there. Armstrong’s Jewish manager and close friend, Joe Glaser, was quoted in LaMerhav saying, “It will be our pleasure never to return to Lebanon,” in response to the boycott.

Louis Armstrong and His Jewish Family

In 1970, just a year before his death, Armstrong was hospitalized at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, a Jewish institution, where he received treatment from Jewish doctors. It was there that he began writing his memoirs. He dedicated the book to his manager, Joe Glaser, whom he described as “the best friend I ever had.”

The first chapter is titled: “Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, La., the Year of 1907.” In it, Armstrong reflects on his relationship with the Karnofsky family, his childhood in New Orleans, his thoughts on the Jewish people, and the differences he perceived between the Jewish and Black communities in the United States.

Although the Karnofskys were white, Armstrong understood early on that this did not shield them from prejudice and antisemitism in early 20th-century New Orleans. He wrote of how, even as a child, he noticed the disdain that other white residents held toward Jews. Over time, he also came to recognize that antisemitism was present within his own Black community as well.

These realizations, and his observations of how the two communities confronted discrimination, deepened Armstrong’s respcet for the Jewish People. “I had a long time admiration for the Jewish People. Especially with their long time of courage, taking so much abuse for so long. I was only seven years old but I could easily see the ungodly treatment that the white folks were handing the poor Jewish family whom I worked for.”

He even took it further, suggesting that the differing degrees of success between the Black and Jewish communities, and the resulting tensions between them, were rooted in social unity. “The Negroes always hated the Jewish people who never harmed anybody, but they stuck together. And by doing that, they had to have success.”

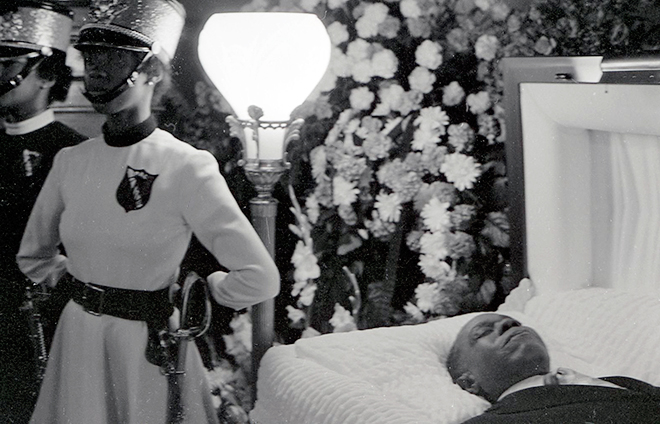

In July 1971, just one month before what would have been his 70th birthday, Louis Armstrong died in New York.

Throughout his life, on every stage from New Orleans to Paris, a Star of David pendant sparkled around Armstrong’s neck. For him, it was not a religious or Zionist symbol, but a personal reminder of the poor child he once was – a child who was given a hot meal and an opportunity by a humble Jewish immigrant family, and who used that opportunity to change the world of jazz forever.