On the day that marked the official founding of what would one day be called the National Library of Israel, the residents of the Land of Israel were consumed by alarming rumors of a deadly disease spreading from distant Russia.

In the city of Saratov, doctors were said to be burying patients alive—so claimed a “telegram” reported in the Hebrew newspaper HaZefirah. The rumors triggered violent riots that left a number of people dead. Meanwhile, another Hebrew paper – HaHavatzelet – expressed concern over a new “inspection order” imposed by the Ottoman authorities on ships arriving “from Russia to Togarmah” (at the time, Turkey was often referred to as “Togarmah” by some members of the Jewish community in the Holy Land– M.Z.), and over the quarantine enforced on the ports of Acre and Haifa.

Still, not everything that day—July 15, 1892—was doom and gloom. The same issue of HaHavatzelet also reported the opening of the Midrash Abarbanel Library, a small institution that would one day evolve into the National Library of Israel. There was even a report on the construction on the Jaffa–Jerusalem railway, which was making “great strides” according to the paper.

All of this information doesn’t come from a scholarly monograph or a rummage through a dusty archive—it’s the result of a quick, casual search on a smartphone. The source? The Historical Jewish Press website, launched 20 years ago by the National Library of Israel in collaboration with Tel Aviv University.

Spanning 250 years, containing millions of newspaper pages in nearly every language Jews have spoken or written, the site gathers it all in one place—accessible to everyone, thanks to cutting-edge digital tools.

Today, the Historical Jewish Press website is the largest digital collection of Jewish newspapers in the world. It offers a wide-ranging, richly textured view of Jewish and Hebrew life over the past two and a half centuries. Whether you’re a serious researcher looking for information on historical figures or events, or simply curious about what dish soap Israeli housewives were using the day you were born—you can open your phone or computer and take a look back in time. Here, we invite you behind the scenes of this remarkable project.

It’s the late 1960s. A 17-year-old boy walks beneath the scorching Jerusalem sun along Keren Kayemet Street, his mind preoccupied with the existential dilemmas of the State of Israel. There were the ever-present external threats, the ones everyone was always talking about. But there was also another issue—less spoken of, but which he saw daily in his own neighborhood of Nahalat Achim: the ethnic divide of Israeli society. It would take years before people began discussing it openly.

That boy was Yaron Tsur.

Today, he is known as Professor Emeritus Yaron Tsur, Israel Prize laureate. But let’s not jump ahead just yet.

Tsur was born just over a month after the State of Israel was founded, into what he calls a “mixed” family: a German-born yekke father, whose last name was so difficult for immigration clerks to pronounce that it was quickly changed to “Tsur,” and a Yemenite mother.

East and West met, naturally, in the Land of Israel. The cool-headed yekke was riding his bicycle through the city when a dark-haired young woman appeared in his path. He fell—literally—off his bike and onto the sidewalk. Over time, that fall took on a deeper symbolic meaning.

“They were a couple of lovebirds—completely in love,” Tsur told us in an interview at his Tel Aviv home, following the Israel Prize announcement. “There was a lot of love in our home.”

That home, where he grew up, was an apartment in a building owned by his grandfather, David Ben Shalom. It was there that he developed the unique worldview that would later define his academic and intellectual work.

David, Tsur’s grandfather, had been a blind child with no real prospects for the future—until he was taken in by the founders of Jerusalem’s “School for the Blind.” There, he learned trades like basket weaving and met Sarah, who would become his wife.

In their early years together, the couple could afford little more than tomatoes—at least according to Sarah’s stories to her grandchildren. But things eventually stabilized. They bought a plot of land, built a home, and over time expanded it into a rental building that provided them with an income. Their tenants were immigrants from all over the world, and the building was managed with a firm but fair hand by its two “great patriarchs”: Mizrahi owner David Ben Shalom and his Ashkenazi tenant, Dr. Sternbach.

“And yet,” Tsur says, recalling his feelings as a child of mixed heritage, “I never felt entirely at ease. I sensed something in the air—something between those Ashkenazis, the white people, and the brown and black people. Nothing openly hostile ever happened to me. I was never directly harmed by what would later be called ‘the ethnic issue.’ Because my father was a yekke, we were classified as Ashkenazi despite my mother’s background. But I remember that atmosphere—and I remember how much it weighed on me, even back then.”

Although the issue deeply occupied his thoughts, Tsur had no real way to act on it. So life moved on. He studied music, joined the IDF’s Intelligence Corps, was discharged, and began writing radio dramas for children.

It was only in the 1970s that the issue resurfaced—this time in an academic context.

Tsur began teaching at the newly established Open University and was assigned the introductory course on modern Jewish history. Though he lacked formal academic training in the field at that time, he had an enormous store of knowledge from years of intensive reading—and an unmistakable passion for the subject.

To his dismay, he discovered that more than five-sixths of the course focused almost entirely on Ashkenazi Jewish history. What had happened to the Jews of Islamic lands before their arrival in Israel? That vast history was relegated to a single sixth of the curriculum.

When Tsur looked for source material to help correct the imbalance, the situation only became more frustrating. He turned to the Jewish National and University Library (as the National Library was known at the time) and was given a towering stack of Ashkenazi-focused bibliographies—alongside a meager, almost negligible pile representing everything else.

So, he created what didn’t exist. He wrote new educational materials himself—some of which would later be used by Israel’s Ministry of Education—or turned to fiction, like the novels of Albert Camus, to teach students about life in North Africa. The students, it turned out, were far more engaged by Camus than by standard academic texts.

It was only natural that the Jews of the Middle East and North Africa would become the central focus of Yaron Tsur’s academic career. His graduate and doctoral work both explored the history of Tunisian Jewry.

In the 1990s, Tel Aviv University became his academic home base. There, he led the “The Jews of Islamic Countries – Archiving Project.” Under his direction, the project gathered an extensive collection of source materials, including historic newspaper issues and writings by Jewish intellectuals from the Maghreb—some in Judeo-Arabic, others in Hebrew, and occasionally even in periodicals published in Eastern Europe.

On Wednesday, July 28, 2004, Orly Simon, who today is head of the Library Processes Division at the National Library, received an email from an unfamiliar academic. It began:

“Dear Sir or Madam, I would appreciate it if this message could be forwarded to your project director. My name is Dr. Yaron Tsur. I teach in the Department of Jewish History at Tel Aviv University and head the Jews of Islamic Countries Archiving Project. I believe the projects we are working on could be excellent candidates for collaboration.”

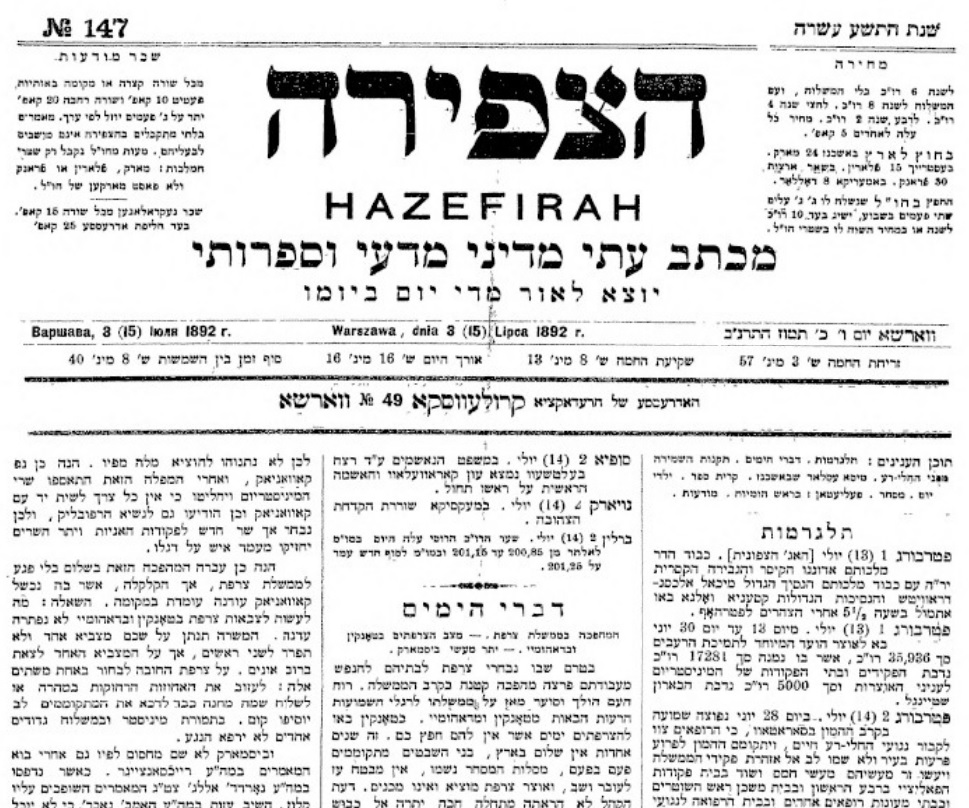

At the time, the National Library had just launched its “Hebrew Press” website—an early digital initiative that offered scanned pages of pioneering Hebrew newspapers: the publications of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and other Hebrew- and Zionist-oriented newspapers from the diaspora, such as HaZefirah, HaMagid, HaLevanon, HaHavatzelet, and others. The site did not yet support full-text search; users could browse scanned pages but not search the content itself.

Meanwhile, at Tel Aviv University, Tsur was overseeing a project that had digitized historical editions of The Palestine Post using new technology that could recognize and index text. Connecting the two efforts was the first step toward what would eventually become the Historical Jewish Press website—today home to millions of newspaper pages in dozens of languages.

The collaboration proved fruitful. Though naturally, there were challenges—technical, logistical, and cultural—they were overcome with determination and good will. Tsur began commuting twice a week to the basement of the National Library in Jerusalem, while Simon recalls making trips to Tel Aviv carrying hard drives packed with precious data.

Initially, the two sites operated side by side. Material digitized by the Library was shared with the Tel Aviv University website, and vice versa. Over time—and after carefully navigating political and institutional sensitivities—the decision was made to unify efforts. A single, independent, shared platform was created: the Historical Jewish Press site, also known occasionally as JPress.

The obstacles were formidable, spanning multiple areas of expertise: new and unfamiliar digital tools; fundraising from foundations; complex legal questions regarding intellectual property; and, perhaps most challenging, reaching out to rights holders—from the publishers of major newspapers to descendants of obscure and long-defunct ones—and persuading them, in many languages and with creative arguments, to participate.

The teams from both institutions—the National Library’s representatives and the Tel Aviv group working alongside them—operated in full partnership. As lead historian, Tsur directed the editorial and curatorial side, including the search for new, historically significant titles to add to the archive.

Projects of this kind require a special kind of devotion—and the Library had just the person: Israel Weiser z”l. For many years head of the Library’s photography department, Weiser joined the project wholeheartedly. He took on one of its most tedious but critical tasks: bibliographic completion. He traveled the globe photographing Hebrew manuscripts, delving into Jewish archives and libraries in pursuit of, say, issue no. 67 of an obscure American-Jewish newspaper missing from the Library’s holdings. He worked page by page, issue by issue, building the archive with care and precision. The exceptional quality and depth of the collection owe much to his efforts.

Naturally, there were also ideological debates along the way. Should the focus be on Hebrew newspapers—those published in Eastern Europe and later in the Land of Israel? Or, as Tsur envisioned, should the project embrace Jewish press from across the globe, in every language and from every community—without bias or hierarchy? In Tsur’s view, even the most obscure corners of Jewish publishing deserved a place in the collection.

In the end, that broader vision prevailed—though the early Hebrew newspapers received special attention. One of the crown jewels of the collection is HaMe’assef, the journal of the Jewish Enlightenment movement in late 18th-century Germany. The first generation of Haskalah thinkers became known as the “Me’assefim,” after the journal. The oldest issue in the Library’s collection dates to 1783.

In 2010, the new unified site was launched quietly (a more public celebration would follow three years later). By then, the archive already featured over 400,000 newspaper pages. The eventual addition of major Israeli newspapers like Davar and Maariv marked a turning point. Today, the site includes millions of pages from Jewish newspapers around the world.

The Historical Jewish Press website has become one of the most important resources available for the study of Jewish life across time and geography. It provides access to rare and once-inaccessible newspapers, preserving the voices of communities large and small.

Here in the National Library’s Digital Department, we also rely on this archive constantly as a foundational tool for our own research and storytelling.

Want to try it yourself? Head over to the Historical Jewish Press search engine—and begin your own journey through the headlines of yesterday.