“Laughter is good for both the health of the body and the soul; the wise doctors have prescribed laughter.”

(Sholem Aleichem)

When Sholem Aleichem was a small boy, the home owners of the town where he grew up would gather at his father’s house on Saturday nights. These bearded Jewish men, with ample bellies, would come together for an evening meal marking the close of the Sabbath – Melaveh Malkah. The image of these gatherings was etched deep into the young boy’s memory, and would, in many ways, shape the course of his life.

He remembered how his father would pull from his pocket a small, well-worn book. Its pages were torn loose from the binding, smudged, and creased from years of use. Sholem Aleichem could no longer recall the book’s title or its author, but the impression left by those evenings would never fade. This is how he described the scene:

“…they burst into laughter, shaking with mirth, clutching their bellies and rocking back and forth. They interrupted the reader constantly with cries of admiration and playful curses aimed at the author: ‘What a clown! May his name be blotted out! What a rascal! May his bones be scattered! What a scoundrel! May a plague strike the father of his father!’”

(From Sholem Aleichem’s autobiographical work, published in Hebrew as Hayei Adam [“The Life of a Man”], translated by his son-in-law Y.D. Berkovitch.)

Young Sholem Aleichem would watch this scene unfold, not yet understanding what his father was reading aloud – but utterly captivated by the bearded men convulsing and holding their stomachs with laughter, their faces glowing with joy. As he gazed upon their radiant expressions, he became extremely jealous of the Jew who had authored this wonderful book, and a powerful longing welled up within him: one day, he too would write a story – one that would cause Jews to read and laugh heartily, cursing the author with glee and good humor.

This early childhood memory offers a glimpse into what would become the hallmark of Sholem Aleichem’s literary career: simple, folk humor – disarming and heartfelt – that spoke to both the joys and the hardships of Jewish life.

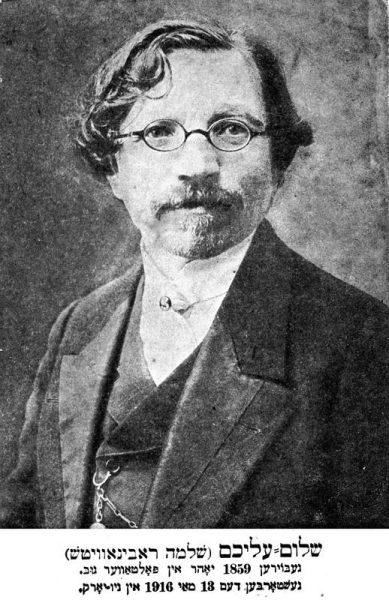

Solomon Rabinovich was born in 1859 in the small town of Voronkov, then part of the Russian Empire (today Ukraine). On this real town he would later model the imaginary shtetl of Kasrilevke, which appears in many of his stories. He was one of six children. His father, Menachem-Nukhem, was a learned man who had turned to secular studies; his mother, Chaya Esther, died shortly after his bar mitzvah.

After completing school, Rabinovich worked as a private tutor – and it was in this role that he met Olga (Golda), who would become his wife and the mother of their six children. A master of Hebrew, Rabinovich began publishing articles in Ha-Melitz and Ha-Tzefirah, which catered to the modern Jewish intellectual elite.

Later, he began writing for Yiddish publications as well. Yiddish was the common spoken language among the Jewish masses of that time. Among other things, he wrote humorous essays on current affairs (feuilletons), and at that point adopted the pen name that would remain with him always – “Sholem Aleichem,” taken from the traditional Hebrew greeting “Shalom aleichem,” (peace be upon you) to which one replies “Aleichem shalom” (upon you be peace). In Yiddish the greeting is pronounced sholem aleichem, and depending on tone it can sound neutral or slightly ironic. The name fit his literary persona perfectly – it is a greeting extended to someone coming from outside (not for someone you know well or met yesterday), a kind of merry jester who carries along a good spirit from elsewhere, whose presence seems to wander about, reaching everyone and knowing all.

Sholem Aleichem accomplished a great deal in his 57 years. He was a writer, playwright, journalist, critic, and editor – and even dabbled in the stock market, though he lost the entire fortune he had inherited from his wife’s father (an episode he later wrote about in his book Menakhem Mendl). Today he is remembered as one of the “three greats” of Yiddish literature, alongside Mendele Mokher Seforim and I. L. Peretz. Though contemporaries, Mendele was called “the grandfather,” Peretz “the father,” and Sholem Aleichem “the grandson.” His works remain a treasured part of Jewish culture, thanks to the way they depict and preserve the memory of the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe – the shtetls where he grew up – and the rich cultural and social world that flourished there, much of which was destroyed in the Holocaust.

Throughout his work, Sholem Aleichem wrote about the simple life of the Jews in the shtetl, with all its charm and its many hardships. The characters he portrayed were ordinary folk, struggling with the grinding burdens of daily life as Jews in the Pale of Settlement experienced it – poverty and persecution, hardship and worry, oppression and despair. He seemed to speak in their very voices, capturing their everyday language, lively and constantly evolving. Humor – like a special seasoning – hovered over it all.

Many of Sholem Aleichem’s stories are fundamentally sad, difficult, and painful. There was much sorrow in the lives of Jews struggling to survive. Yet none of his stories leaves the reader pessimistic or broken. He told these sad tales with charm, in enchanting words and a tone that makes the reader laugh and momentarily forget the sadness that is always present – never hidden, not even for a moment.

The magic of his words lay largely in the way his humor provided a temporary escape from all those hardships. One day, a Jewish man approached Sholem Aleichem, kissed his hand, and said: “You are our comfort – you sweeten for us the bitterness of exile.”

His Muse: A Hot-Tempered Stepmother

Where did Sholem Aleichem acquire this remarkable ability to create such unique characters, with humor so sharply attuned to his voice? In his book Hayei Adam, an entire chapter is devoted to his hot-tempered stepmother, who would beat him and his siblings and pour out her wrath upon them with vigorous curses and insults. Sholem Aleichem did not allow these painful experiences to crush his spirit – instead, he channeled them into creativity. At night, by candlelight, he wrote a complete dictionary of the “pearls” that issued from her mouth, organized alphabetically.

Under the letter Alef (A), he included curses such as:

Evyon (pauper), avi-avot ha-tum’ah (progenitor of impurity), even-negef (stumbling block), avrekh meshi (silk yeshiva boy), evil sefatayim (babbler), akhlan (glutton), alontit lakhah (wet towel), asufi min ha-shuk (foundling from the marketplace), askupah nidereset (doormat), apikores (heretic), efrokh (fledgling), arkhi parkhi (tramp), Ashmedai (demon), atono shel Bilam (Balaam’s donkey)…

(From Hayei Adam)

He even noted their tone and intonation, as they were often delivered in rapid-fire bursts:

Every word was accompanied by a curse, delivered good-naturedly. For example: If she said “eat,” she’d add: May the worms eat you! Drink: May leeches drink your blood! […]

Sometimes when Stepmother was in a good mood and latched onto a word, she’d twist it and turn it and stretch it like dough – there was no stopping her. She’d let it out in one breath, like the Megilla reader rattling off the ten sons of Haman on Purim, and in rhyme no less:

‘God Almighty, may you be bitten and smitten, eaten and beaten, sell and yell; may you get gout and shout, have aches and breaks and itches and twitches, dear merciful Father in heaven!'”

(From From the Fair)

The dictionary, written in Sholem Aleichem’s neat hand, somehow ended up in his father’s possession. Sholem Aleichem trembled at the thought that his stepmother might read it – but to his great surprise, she burst out laughing. Amused particularly by the name-calling, she began calling him korkeban (gizzard) because of his short stature.

His stepmother was only the first – in all his later works, every character was infused with distinctive humor. The same is true of his most famous creation, Tevye the Milkman, the series of stories that inspired the musical Fiddler on the Roof. Tevye, is known for his constant use of Biblical and Talmudic quotations. But these are no ordinary quotations – they are playful, distorted, invented versions of the originals, creatively adapted to whatever situation Tevye finds himself in, always serving to lift his spirits. “Every sorrow he softens with a verse,” wrote one critic. And when needed, Tevye adjusts the verse to suit the new circumstances of his life.

But Sholem Aleichem was not a satirist. He did not laugh at his characters, but with them. It is well known that very little separates laughter from tears. The famous line from Motl, the Cantor’s Son, Sholem Aleichem’s final work, left unfinished at his death, sums this up perfectly: “Lucky me! I’m an orphan!”

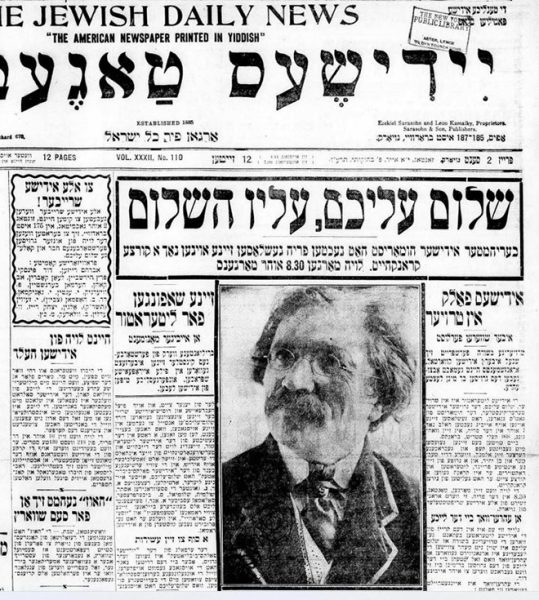

Breaking Into Laughter at the Gravestone

Sholem Aleichem saw himself as a humorist – and that is how he wished to be remembered. He did not leave this to chance, but made his wishes clear both in his will and on his gravestone at Mount Carmel Cemetery in New York. He passed away in 1916, and hundreds of thousands of admirers who had grown up reading his books accompanied him on his final journey. The funeral procession lasted half a day, beginning in Harlem, passing along Fifth Avenue, moving into the East Side, and from there continuing to the Jewish cemetery in Queens.

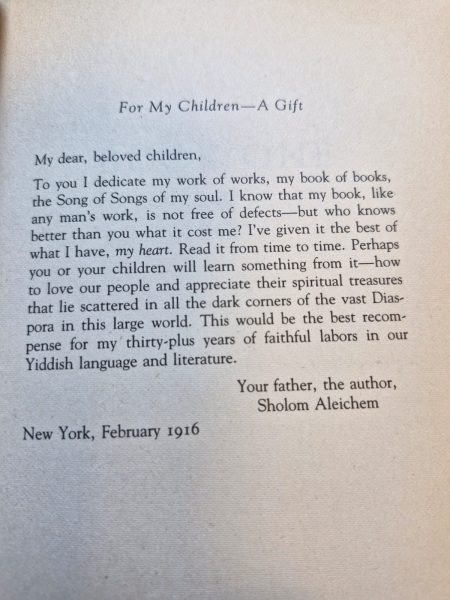

In his will, Sholem Aleichem left clear instructions:

“Wherever I die, do not lay me to rest among the great, the noble, or the mighty, but rather among the Jewish working folk, among my own people. Let the gravestone that will be erected over my grave serve to honor the humble graves around it, and let those humble graves in turn adorn my own, just as the simple, honest Jewish masses honored their writer in his lifetime…”

He further wrote that on the anniversary of his death, when his family and friends would visit his grave:

“Let them choose one of my stories – one of the most cheerful – and read it aloud in whatever language they best understand. It would be better for my name to be remembered with laughter than not remembered at all…”

Sholem Aleichem also wrote his own eulogy. At the age of 46, eleven years before his death, in his New York home, he composed a poem of mourning for himself in Yiddish. He asked that it be translated into Hebrew under his supervision. After his death, it was engraved, as he had wished, on his gravestone:

“Here lies a simple Jew,

Who wrote Yiddish tales to gladden the hearts

Of the common folk and their women –

Here lies a humorist.

All his days he loved to jest

About the world and its creatures.

The whole world prospered –

But he wasted away in suffering.

And when the world laughed aloud,

Clapping hands with joy,

His soul wept in secret

To the Almighty in Heaven.”

The wills – both private and public – that Sholem Aleichem left behind leave no doubt as to how he viewed himself as a writer, and what he hoped to leave for his family after his death. His words scatter his special magic – humor – on the wind, so that it might reach us too, in the future. This same humor helped make the hardships of life, the sorrows of circumstance, and the wearying disasters faced by hundreds of thousands of his readers just a bit more bearable.

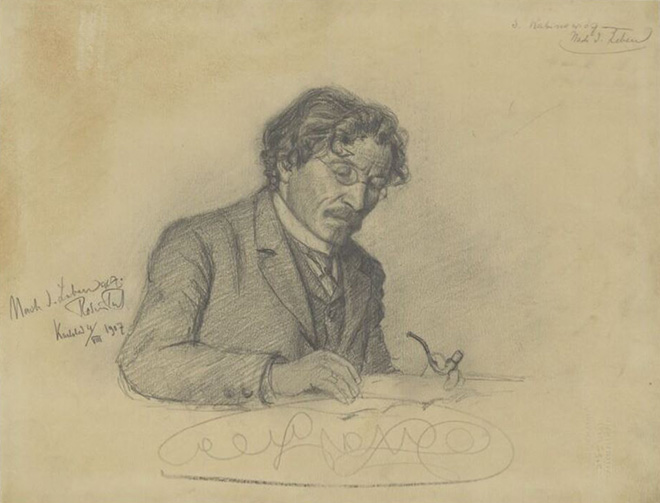

For writing was Sholem Aleichem, and Sholem Aleichem was writing. It consumed his entire existence and all of his time:

“I have advanced so far in my illness, this illness of writing, that I now belong not to myself or my family, but rather to our literature and to that large family called the audience…”

And we are left with the gifts he gave us. Perhaps this is the gift we need most of all – to laugh. Because if not – all we can do is cry.

***

Recently, a unified Yiddish catalog has gone online – a joint project of four libraries with large collections of Yiddish books and periodicals: YIVO (Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut), YBC (Yiddish Book Center), NYPL (New York Public Library), and the National Library of Israel.

This cultural collection now contains over 45,000 items and aims to create a complete catalog of all Yiddish books and periodicals ever published, enabling users to search all library holdings in one place. Unsurprisingly, Sholem Aleichem ranks first for number of works returned in catalog searches (501).

In preparing this article, the following sources were consulted:

“The Commandment of Laughter – The Humorous Works of Sholem Aleichem” by Prof. Adir Cohen, Ma’agalei Kri’ah, no. 30, May 2004;

Dan Miron, “The Meaning of the Literary Name ‘Sholem Aleichem’,” Haaretz, June 17, 2016;

and an anthology compiled by Matan Hermoni, Sholem Aleichem, Sal Tarbut Artzi, 2009.