“‘Kichka’ doesn’t come from the word ‘kishkush‘ although some people think that because of my drawings,” explains cartoonist, caricaturist, and illustrator Michel Kichka at the beginning of our interview, referring to a word in Hebrew that can mean both ‘doodle’ and ‘nonsense’. We spoke during a warm and often funny phone conversation ahead of the screening of Kichka: Telling Myself at the recent Docutext Documentary Film Festival at the National Library.

Kichka, who celebrated his 71st birthday on August 15, proves to be, unsurprisingly, a humorous, honest, and friendly conversationalist. He is a devoted family man, a passionate Zionist, and a committed humanist who never stops learning and evolving. As he speaks, the stories flow easily, one leading into the next, and by the end of the conversation it’s clear: Michel Kichka’s artistic work is deeply and inseparably linked to the person he is.

***

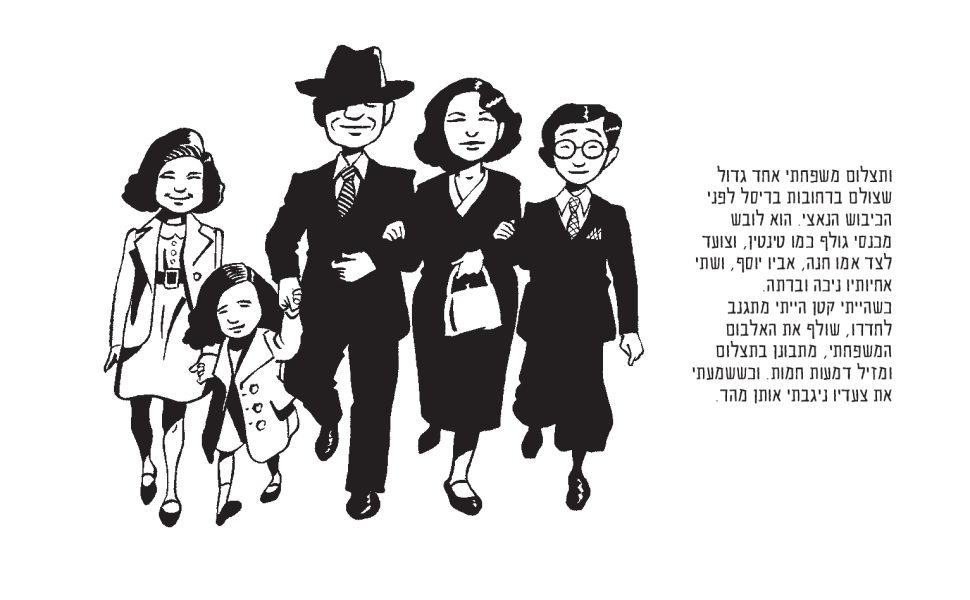

There aren’t many people in Israel with the last name “Kichka,” if any at all. “My father was the only Holocaust survivor in his family, and he was very proud of that name. He wanted the family line to continue. He was thrilled when I was born, his first son, because he knew our name would live on,” he recalls. “I had three sons, and with each one he felt like he was defeating the Nazis.”

This optimistic story is grounded in a more difficult reality. Both of Kichka’s parents were Holocaust survivors who wanted a family but struggled with the day-to-day demands of raising children. Michel and his three siblings were sent to live in boarding schools.

Did he always know he would become an artist? I asked. “Already in first grade, when they asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said I wanted to draw. I didn’t even really understand what that meant.” He adds, “As I got older, I had the sense that my father would have liked to be an artist, but it wasn’t a practical choice. He was always focused on survival. Only when he retired did he finally have time for it. I always felt like I was fulfilling that dream for him.”

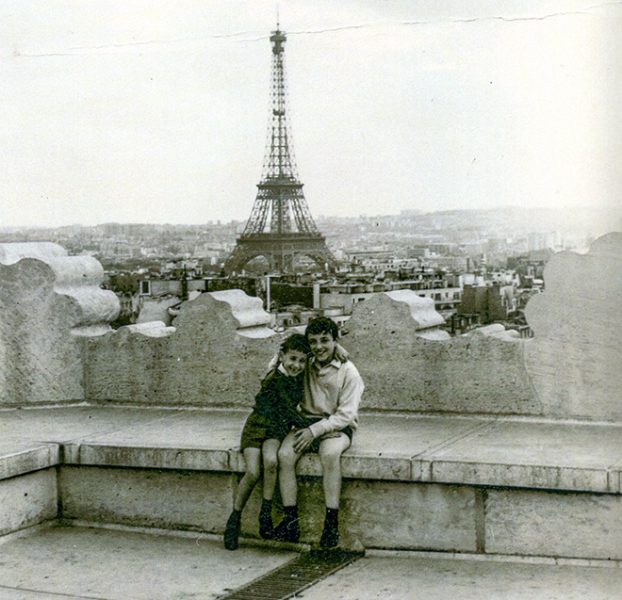

Kichka began living that dream already in his youth. Growing up in Belgium, where the capital Brussels is often considered the mecca of the comic world, Michel quickly fell in love with graphic novels and comic books. “Across from our house was a used bookshop where I could buy secondhand comic books. That was all I could afford with the small allowance I got. At the train station I used to travel through to boarding school, they sold little comic booklets too. I would buy those and trade them with kids at the school, so I could read more.” In high school, he published his own comic strips, although he never formally studied illustration.

At 15, he fell in love, not with a Belgian girl, but with a young country: Israel. In his hometown near Liège there weren’t many Jews. His parents were secular, and there was only one Jewish youth movement in the city: Hashomer Hatzair. At 15, as was customary for members of the movement, Kichka traveled to Israel to take part in a summer camp along with a group of companions. He volunteered on a kibbutz for six weeks. It was the summer of 1969. Israel was still riding high after the Six-Day War, and the sharp contrast between his gray, rainy, industrial hometown and the sun, sand, and freedom of Israel captivated young Kichka. Even then, he knew he wanted to live here.

In Israel, he also stumbled upon a Tel Aviv kiosk selling issues of MAD Magazine, which became the second major influence on his artistic style, alongside the Belgian comic tradition of Tintin and friends.

At 19, already studying architecture in Belgium, he made a life-changing decision. His older sister had moved to Israel and joined a kibbutz. During a visit to see her, he heard about Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and decided to apply. In a seven-page letter (which he still keeps), he explained his idealistic decision to his disappointed parents. “The Yom Kippur War broke out, and I felt that this was the time to come – the country was in crisis, and I wanted to help build the place and to make something of myself. Not as a slogan, but truly. And that’s what happened. In Israel I met my wife, Olivia. I built my career. I became Israeli. I knew I was coming here to stay.”

Young Kichka decided to leave architecture behind and pursue illustration and comics. But he hadn’t realized that he’d have to actually be accepted to Bezalel. He arrived with his beginner’s Hebrew – fresh from ulpan (Hebrew school) – and a portfolio filled with comic sketches. Still, he was admitted. Since Bezalel had no dedicated tracks for illustration or comics at the time, he enrolled in the graphic design program. “People in Israel had a lot of prejudice toward comics. They thought it was lightweight entertainment for the masses, lowbrow culture mostly for kids. There was hardly any comics scene in Israel – just Dudu Geva and Uri Fink’s Zbeng, maybe tucked in the back of the newspaper, if that. But I didn’t care. I knew I would make comics. I couldn’t not do it.”

Eighteen years later, in 1992, Bezalel asked him to open a course on comic illustration. He taught it until his retirement in 2024, nurturing a new generation of top Israeli graphic storytellers, including members of his very first class: Yirmi Pinkus and Rutu Modan.

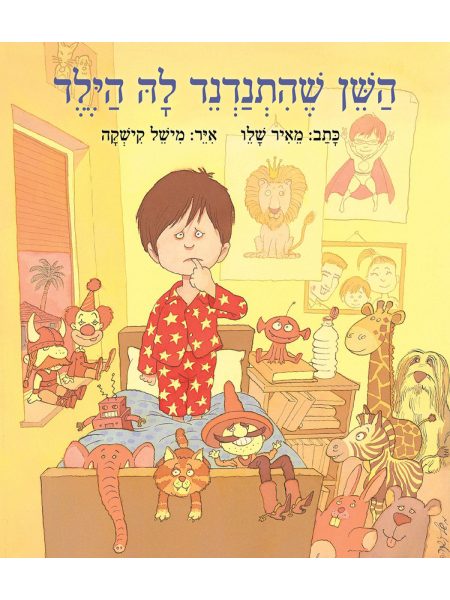

Beyond teaching, and creating comics and editorial cartoons, Kichka has illustrated dozens of books for children, teens, and adults – including works by some of Israel’s greatest writers: Uri Orlev, Ramona Dinur, David Grossman, Nira Harel, and A.B. Yehoshua. One of the last books he illustrated was The Tooth That Had a Wobbly Kid by Meir Shalev, with whom he worked just before Shalev’s passing. “Working with him wasn’t always easy, but it was a fascinating experience,” Kichka says. “He knew exactly what he wanted. He had a clear vision. After I illustrated The Tooth That Had a Wobbly Kid, he wanted to work with me again, and while we were working together on Karate Boy I realized he was very sick. It was sad and moving. He managed to approve the final drafts, but passed away before the book came out.”

Kichka lives, thinks, dreams, and creates in two languages. In his early years in Israel, all he cared about was becoming Israeli, along with his French partner, Olivia. “We didn’t know anything. At our eldest son’s Hanukkah party in kindergarten, we didn’t recognize a single song. We learned everything together with the kids. In [Europe], they don’t celebrate all the holidays they celebrate here, and certainly not in the same way.” But he never erased his past, his memories, or his mother tongue: “Being bicultural is an enormous privilege! I know there was once a tendency in Israel to reject anything seen as Diaspora-related. Maybe I was lucky I didn’t end up in a kibbutz like my older sister – I’m not sure they would have let me speak French with my kids there.”

Life in Israel may have seemed peaceful for Kichka and his new family, but the family secrets that had surrounded him since childhood were always there in the background. His world shattered when his beloved younger brother, Charly, took his own life. Michel was 34 at the time. “I felt like a part of me died with my brother. I raised him, I was the protective older brother, the one who supported him. My parents weren’t really there for him – I say that as a fact, not out of blame. Then, during the shiva [week-long Jewish mourning period], my father started talking about himself – about what he’d gone through during the Holocaust. But I just couldn’t hear it. I was furious with him for choosing the shiva as the occasion to share that story, and I was broken.”

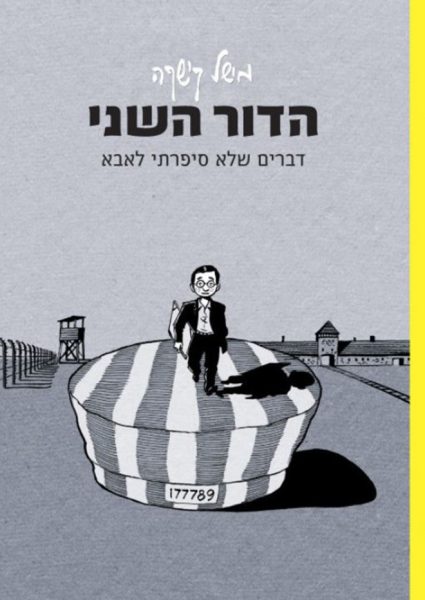

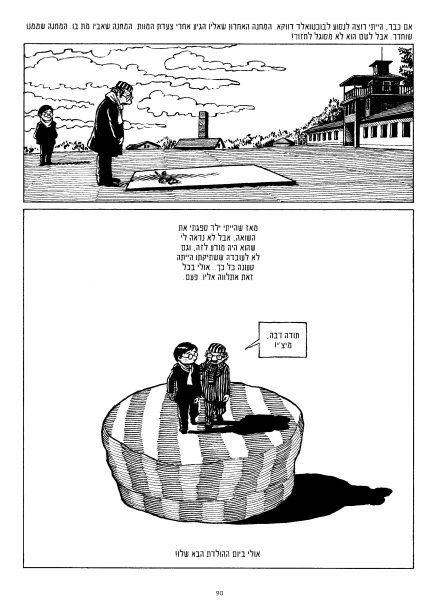

For years, Kichka carried within him the seeds of a major, deeply personal work – a way to process the rupture within his family. He found inspiration in Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, the acclaimed graphic novel by Art Spiegelman, which opened the door for comics to be recognized as a literary form not just for children.

The idea had been with him for years, simmering inside of him, but he couldn’t seem to bring it to life. Eventually, it was his wife Olivia who gave him the push he needed: “You have to decide,” she told him. “Either you do it, or you stop saying you’re going to do it.” That was the jolt he needed. “I knew for sure,” he says, “that if I didn’t do it, I’d spend the rest of my life regretting it.”

The process of creating Second Generation: The Things I Didn’t Tell My Father changed his life: “For the first time in my life, I was the one writing. It was the most incredible period I’ve ever experienced. I discovered the joy of writing. I realized I remembered far more than I thought. It was like one memory would call forth another – like a muscle growing stronger. I worked like a man possessed, 18 hours a day for a year and a half. I just couldn’t stop.”

The graphic novel Second Generation: The Things I Didn’t Tell My Father was published in 2012, first in French for European audiences, and later in Hebrew. It was translated into several languages. In France, it was adapted into an animated children’s film titled My Father’s Secrets, which was released in 2022.

“The book – and the film that came out of it in France – turned me into something new: a speaker. I now travel with it, sharing the story with all kinds of audiences: at Yad Vashem, with IDF officers, in libraries across Israel, and abroad. It’s amazing to hear people’s reactions, to see how they connect – even those who have no personal link to the Holocaust. Everyone knows what it’s like to carry family secrets and tragedies. The courage to put everything on the page truly healed us.”

The book also helped repair Kichka’s complicated relationship with his father: “When he saw the book, he was in shock. This was a topic we had never spoken about directly – my brother’s suicide. Even after the book was published. That’s how it is in our family. We’re not used to exposing things. I went far with it and put all my pain and criticism of him in the book,” he says.

“I carried criticism towards my parents with me for years. But on the other hand, they were survivors who had suffered so much, and all we wanted, all the members of my generation, was to make them happy and meet their expectations. In the end, the fact that I was able to put it all down on paper, without intending to hurt or blame anyone, just to have it out there, to have it said – that was a big deal. The book helped us all heal.”

After the events of October 7, Kichka knew he had to respond. “I joined Uri Fink’s initiative to create a comic book titled At the Heart of October 7, which tells 12 stories of civilian heroism from that day. The different stories were assigned to comic artists by lottery, and I had the privilege of meeting Youssef Alziadna, a Bedouin bus driver who rescued young people from the Nova party. I illustrated his heroism, and part of our moving encounter made it into the film as well.”

Kichka continues to create even now. “My next project is a work about the genocide that occurred in Rwanda. I was commissioned to create a book – a graphic novel – about one of the genocide survivors. I have a deep sensitivity to human suffering and to what hatred can bring about. That’s a guiding principle for me, and that’s why this is a project I care deeply about. I was invited to Rwanda in 2020 to speak about my work. They learned a lot from us about different ways to commemorate such a painful event for an entire people. There’s a lot of activity and creativity happening there.”

***

The film Kichka: Telling Myself, directed by Gad Aisen, follows Kichka through his journey as a creator who spent years illustrating the stories of others, until he finally dared to tell his own most personal and complex story. His book Second Generation: Things I Never Told My Father is a moving personal account and a family story that has come full circle, one that has touched many hearts around the world.

Kichka saw this deeply personal and revealing film for the first time only after it was completed, during a festive screening in front of a large audience – “I had no idea what Gadi, the director, was doing. He filmed me for dozens of hours over four years. I didn’t know what would come out of it. Honestly, at the start, I didn’t fully understand what I was getting into.”

The talented comic artist allowed the seasoned documentary filmmaker to enter his life and closely accompany him. The film intimately reveals the process of creation, when the illustrator also becomes the writer, and leaves every viewer with a deeper understanding of the meaning of life, and of our ability, with devotion and effort, to heal what was broken in generations past.