The Neilah prayer service was winding down and, with it, the Yom Kippur holiday. Worshippers repeatedly glanced at their watches to gauge how soon they could race home to break the 25-hour fast.

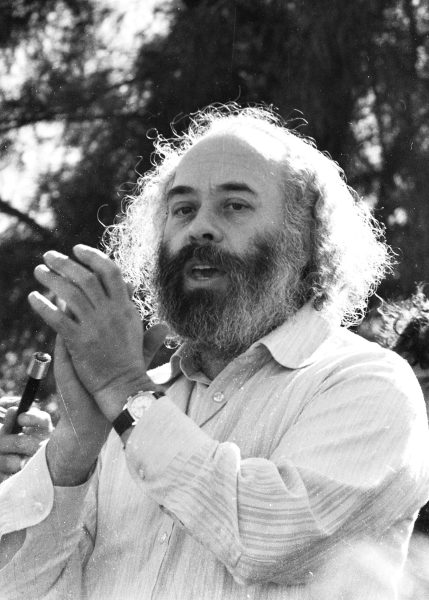

But the man leading the service, Shlomo Carlebach, “was in a trance” of sorts, Ari Goldman remembered, and ignited attendees in spirited singing that kept the solemn day going as people chanted and hugged.

“It was the kind of experience I never had before. It took you out of your body and out of your needs. It’s something I remember and romanticize,” said Goldman, a retired Columbia University professor.

The setting was Carlebach’s synagogue on Manhattan’s Upper West Side on September 15, 1994.

Five weeks later, on October 20, Carlebach died of a heart attack at the age of 69.

Carlebach was dynamic and charismatic, a man who melded music and storytelling, becoming a sort of Jewish pied-piper for the modern age. His goal was to reach Jews across the globe, especially those young and unaffiliated, and connect with their souls.

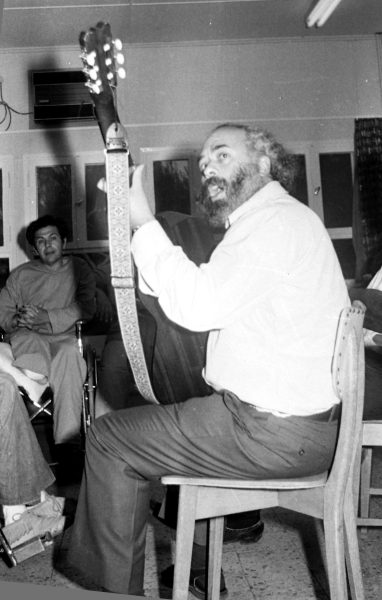

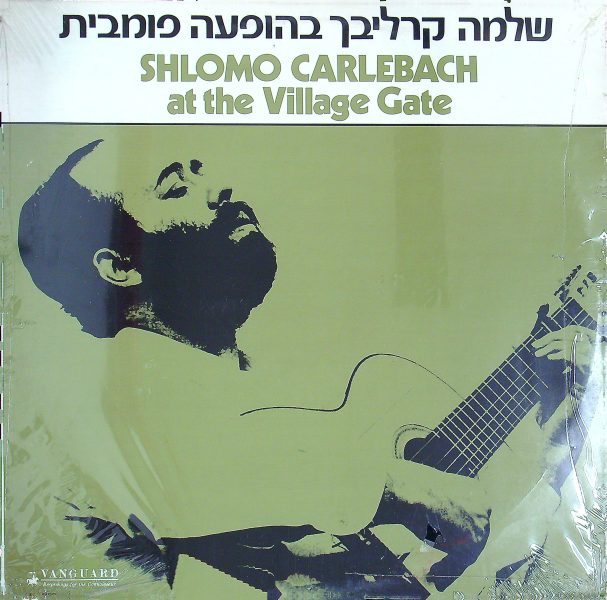

Known as The Singing Rabbi, he crafted simple tunes for equally basic, and exceedingly brief, lyrics often taken from Jewish texts. He would accompany them by strumming a classical guitar. His songs not only caught on and spread, but did so across multiple denominations of Judaism, quickly becoming standard fare at weddings and bnei mitzvah celebrations. Thirty-one years after Carlebach’s passing, they remain so.

Think of Od Yishama B’arei Yehuda (“It Will be Heard Again in the Cities of Judea”), the quick-paced, joyously rising song emitted by a clapping circle of loved ones dancing the groom toward the bride to begin a wedding ceremony. Am Yisrael Chai (“The Jewish People Live”). Eilekha Hashem Ekra (“I’ll Call Upon You, God”). Bilvavi Mishkan Evneh (“I’ll Build a Tabernacle in My Heart”) Hashmi’eini Et Koleikh (“Let Me Hear Your Voice”). All are songs Carlebach composed or popularized.

When Israeli musician Lenny Solomon entertains at weddings and bnei mitzvah parties, “the music we’re playing is naturally Carlebach,” he said.

“They’re songs you have to sing. The musical legacy is un-freaking-believable,” said Solomon, who as a boy in Queens, New York, learned to play Jewish songs on accordion without knowing they were Carlebach’s creations.

“He’s kind of the soundtrack,” said Shaul Magid, a Harvard professor of modern Jewish studies. “Certainly, in post-war Jewish America, he’s one of the two or three most important personalities in terms of influence.”

To Goldman, Carlebach’s songs were “very formative music” that he’d dance to in his family’s living room in New York. Goldman attended Carlebach’s synagogue as a teenager and became “almost like a roadie,” hauling Carlebach’s guitar into and out of taxis they’d take to concerts. “I could not be in his circle enough.”

Carlebach continues to influence Jewish life and prayers. In scores of synagogues worldwide, Friday night services — some once a month, some weekly — are held in what’s dubbed Carlebach-version, with the prayers sung soulfully rather than mumbled by rote.

“He liberated the liturgy from the standard nusach,” Magid, using the Hebrew word for version, said of Carlebach-influenced prayers and life-circle songs.

Carlebach was born just over a century ago in Berlin and as a boy emigrated with his parents to New York. He came from a family of rabbis and became one himself, taking over the Manhattan synagogue after his father’s death and establishing his own in San Francisco in the mid-1960s that he named the House of Love and Prayer.

He had a talent for music, wrote songs and performed in Manhattan nightclubs. He soon combined his passions, melding Hasidic-influenced spirituality into music to connect with Jewish concertgoers. He was lively and personable, someone who cheerfully hugged both men and women.

In the years after Carlebach passed away, several women charged that he had sexually harassed and abused them.

“His life and legacy are so complicated because of all the things that came out after his death and sullied his legacy for some in the generation who didn’t know him,” said Magid, who from 1986 to 1989 lived in the Israeli community Carlebach founded, Moshav Mevo Modiim, and has written several journal articles about him.

That side of the man will be one of the themes of a documentary about his life due out in early 2026 by Manhattan filmmaker Simon Mendes, who said he wanted “to tell the full story of Shlomo Carlebach.”

“It’s either been hagiography or: ‘He should be cancelled. Oh, he’s a sexual predator,’” Mendes, who grew up a few blocks from the Carlebach synagogue and was a child when Carlebach died, said of previous films. “I think it’s important to be honest and to hold both realities.”

Shlomo Katz is another person too young to appreciate Carlebach at the latter’s peak. He did attend one performance when Carlebach came to Katz’s native Los Angeles.

Katz, a musician and the rabbi of a congregation in the Israeli town of Efrat, has spent decades collecting videos and audios of Carlebach’s concerts. He also has published books of divrei Torah (Torah commentaries) spoken by Carlebach between songs of his shows and in lectures and interviews.

“I felt that every word he was singing was connecting me to my soul, to God and the Torah,” Katz said.

Another musician, Lazer Lloyd, even moved to Israel with Carlebach’s assistance soon after they met.

That occurred at the Millinery Center Synagogue in midtown Manhattan, days before Carlebach was due to perform there. Within minutes, Carlebach invited Lloyd to appear with him.

“He asked me what kind of music I played. I said, ‘The blues.’ He said, ‘I play the Jewish blues. You play your blues, and I’ll play mine,’” Lloyd said.

“I was mesmerized from that first concert. I didn’t know I’d meet this influential Jewish guru. He blew me away. I realized Jewish music was very deep. His music was very deep and moving. People were dancing and crying.”

Lloyd had just returned from visiting his sister in Israel. At lunch the day after the concert, he told Carlebach he was considering another trip to Israel. Their conversation spurred Lloyd to decide to study religious texts, so Carlebach arranged for the head of a Jerusalem yeshiva to host Lloyd. In August 1994, Lloyd arrived to begin his studies. Carlebach died that October before they could meet again. Lloyd still lives in Israel, in Beit Shemesh.

Earlier this month, Lloyd performed at Carlebach’s moshav, much of which burned down in 2019.

Carlebach had told Lloyd: “It’s one of my favorite places in the world to play.”

Writer-editor Hillel Kuttler may be reached at [email protected].