Ask a Jewish baseball fan which members of the tribe reached the sport’s Hall of Fame, and the names of slugger Hank Greenberg and pitcher Sandy Koufax will surely be uttered before the query is completed.

Mention that the shrine in Cooperstown, N.Y., added a third Jewish member in 2008, and anticipate quizzical looks.

That may be because the Hall of Famer in question, Barney Dreyfuss, died 93 years ago and wasn’t a player.

Dreyfuss owned the Pittsburgh Pirates for three decades, with the team winning the National League pennant six times and the World Series twice during his tenure. Plenty of owners have presided over teams earning two or more championships during professional baseball’s 150 seasons of existence, so that’s not what paved Dreyfuss’s path to Cooperstown. (Fewer than 10 owners are in the Hall of Fame.)

With Major League Baseball’s championship between the Toronto Blue Jays and Los Angeles Dodgers now underway, now is a good time to consider that Dreyfuss helped to launch the World Series, pitting the champions of the National League and American League. The first World Series was held in 1903, matching Dreyfuss’s Pirates and the A.L.’s Boston Americans (later known as the Red Sox). Boston took the crown, defeating Pittsburgh five games to three.

MLB’s official historian John Thorn sees the “first” designation as nuanced, since the World Series wasn’t institutionalized until two years later.

“Most fans believe that Dreyfuss came up with the idea of the ‘first World Series’ in 1903, but that was merely an agreement between the Pittsburgh and Boston clubs. The first World Series that reflected an agreement between the American and National leagues did not come until 1905,” Thorn said. (A championship series wasn’t played in 1904.)

Dreyfuss’s Hall of Fame plaque is vague, stating that he was “one of the founding fathers of the modern World Series.”

Dreyfuss’s other notable accomplishments included the building in 1909 of Forbes Field, one of baseball’s first two steel-and-concrete stadiums (Shibe Park opened two months earlier cross-state in Philadelphia), a shift from the sport’s prevailing wooden architecture that witnessed numerous fires. Another Dreyfuss stadium innovation that remains standard was the construction of ramps to ease the daily egress of tens of thousands of fans. Dreyfuss named the building not for himself, as owners of the time tended to do, but in memory of John Forbes, a British brigadier general whose capture of a French fort led to Pittsburgh’s founding. The Pirates won their first World Series in Forbes Field’s inaugural season.

Dreyfuss also took a leading role in plotting the schedule of games in both leagues; pushed to appoint a commissioner of baseball, a position that’s been in place since 1920; and was an early advocate of interleague games, a radical notion not incorporated until 1995.

“This was the first person, who was not a player, who was a major force in baseball. He was shrewd [and was] one of the first people to show that baseball could be a viable business,” said Brian Martin, author of a 2021 biography, Barney Dreyfuss: Pittsburgh’s Baseball Titan. “He was a pioneer in terms of the modern World Series and the commissioner. His imprint on the game, his legacy, is lasting.”

Dreyfuss’ path to team ownership and, eventually, the Hall of Fame is intriguing.

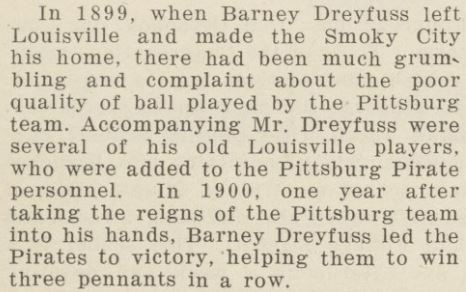

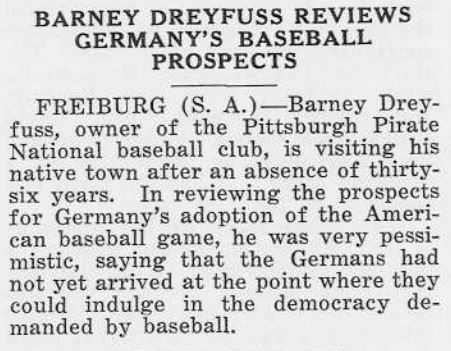

Dreyfuss was born in 1865 in Freiburg in what would become part of Germany. His relatives in Paducah, Kentucky, arranged Dreyfuss’s immigration to the United States in 1881, where he worked as an accountant at their distillery. Dreyfuss’s doctor recommended that he get exercise by playing baseball; it was his first exposure to the sport. After moving with the company to Louisville, Dreyfuss became a part-owner and later full owner of the Colonels baseball team. When the N.L. eliminated the Colonels and three other franchises after the 1899 season, Dreyfuss bought a half-share of the Pirates and transferred Louisville’s best players — including shortstop Honus Wagner, still considered among the greatest baseball players ever — to Pittsburgh.

The Louisville-Pittsburgh machinations demonstrated Dreyfuss’s “making lemonade from lemons” and constitute “his true legacy,” said Thorn, who also was born in Germany.

Dreyfuss was known to bet on horses and frequent racetracks. In one of several books he authored about the era, Pittsburgh historian Ronald Waldo discussed the team’s feud with the New York Giants, an N.L. rival. The quarrel was inflamed, he wrote, by Giants manager John McGraw’s falsely disparaging Dreyfuss for accruing gambling debts.

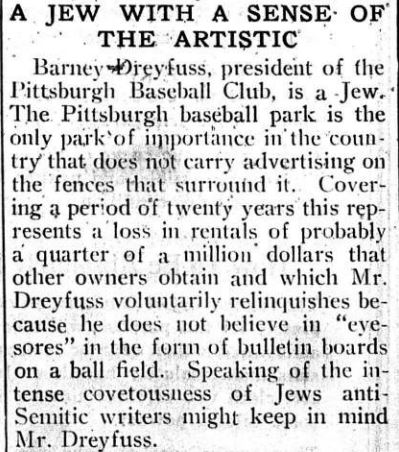

An article appearing in Denver’s Intermountain Jewish News a month after Dreyfuss’s death stated that his “name, word, ethics or sportsmanship were never questioned.” The article below appeared in The Sentinel, a Chicago Jewish paper:

The Pirates, now two stadiums removed from the long-razed Forbes Field, this season celebrated the centennial of the second of Dreyfuss’s World Series-winning teams. That 1925 club is notable as the first to recover from a 3-games-to-1 deficit, defeating one of baseball’s legendary pitchers, the Washington Senators’ Walter Johnson, in the deciding Game 7.

In a telephone interview, Waldo called the 1925 Pirates a “forgotten team” in the sport’s annals. Something similar can be said about Dreyfuss.

“It’s great that he finally got inducted” to the Hall of Fame, Waldo remarked. “I think he should have gotten elected a lot sooner.”

Writer-editor Hillel Kuttler can be reached at [email protected].