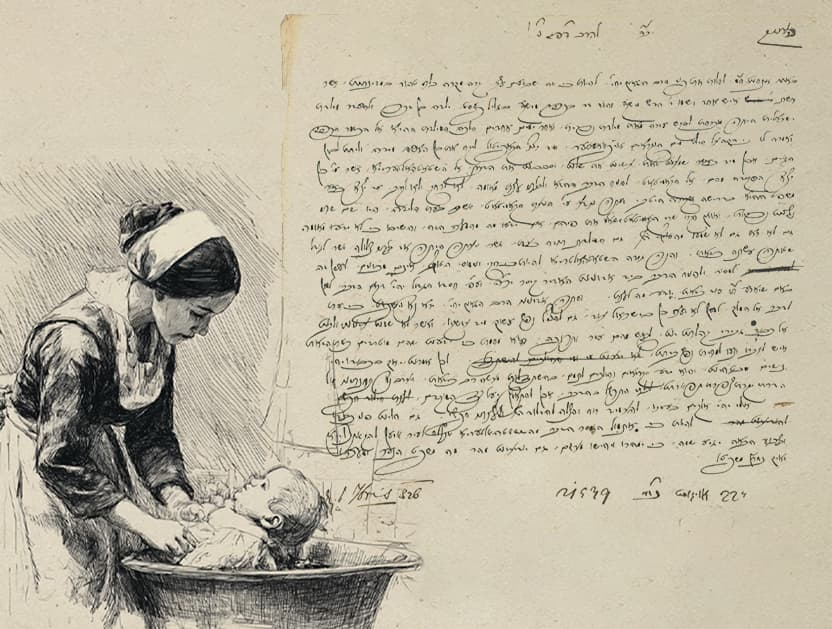

With no Jewish midwife in the village, she turned to a local Christian one for help.

The birth itself seems to have gone smoothly, but a few days later complications arose. The midwife told the village priest that she had baptized the baby, or as described in a letter about the incident, “she sprinkled on the newborn the water known as Taufwasser [baptismal water].” According to Christian belief, baptism leaves an indelible mark on the soul and cannot be undone. Therefore, a baptized child is considered fully Christian and cannot remain in Jewish care.

The local authorities acted quickly, ordering that “the child be taken from the woman and given to the gentiles.”

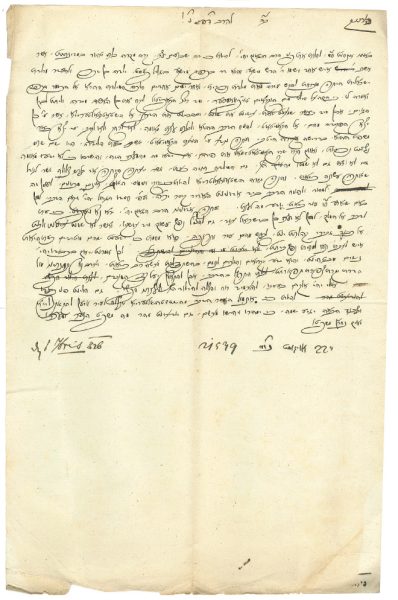

In desperation, the local Jews appealed to the regional imperial authority, the Statthalterei, which instructed them to wait until an investigation was completed. During the inquiry, it emerged that two other non-Jewish women had been present at the birth; both testified that they neither saw nor heard of any baptism. Even the midwife herself later claimed that “her mind was not clear at the time and that, in her great foolishness, she did such a thing.”

Because of these unclear findings and the uncertainty of the law in such a case, the authorities decided to refer the matter to His Imperial Majesty, the emperor himself. The community leaders of Pest sent an urgent letter to the rabbi of Pressburg, asking him to appeal to the emperor – “to come before the king to beseech him so that it is not done so in Israel.” A copy of this letter, dated September 1, 1826 (1 7bris 826), is preserved today in the Hungarian Jewish Museum.

As far as I can tell, this case is not known from any other source, which suggests that the child most likely remained with his family.

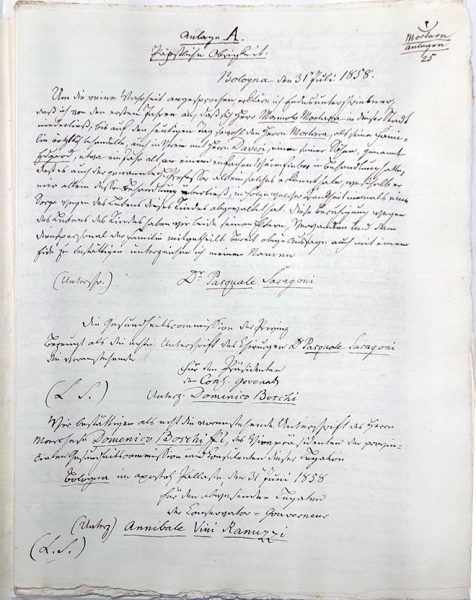

About thirty years later, a similar story took place in Bologna, but there the abducted child was never returned. Edgardo (Gad Yosef) Mortara was six years old when he was taken from his parents after their Catholic servant, Anna Morisi, claimed that she had baptized him during an illness to save his soul. The international outcry that followed failed to change the Church’s decision, and the boy was never returned to his family. Edgardo remained within the Church and later became a Jesuit priest. His story, often called “The Mortara Affair,” is well known, and there is even a separate article on “The Librarians” devoted to it.

The Mortara family gave their documents about the case to the scholar Solomon Ludwig Steinheim (1789–1866), asking him to publish them.

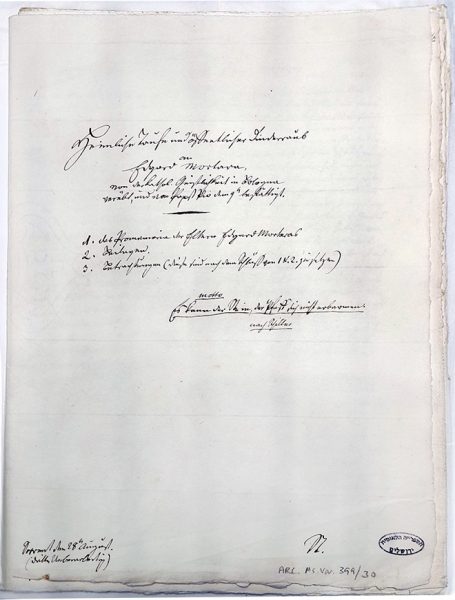

Using these materials, Steinheim wrote a detailed study in German titled The Secret Baptism and Public Abduction of Edgardo Mortara, Carried Out by the Catholic Clergy in Bologna with the Approval of Pope Pius IX. The manuscript is preserved today in Steinheim’s personal archive in the Archives Department of the National Library of Israel (Arc. Ms. Var. 399 03 30) and has never been printed. About thirty years ago, Rabbi Prof. Aharon Sha’ar-Yashuv (1940–2024) wrote in his (Hebrew) book Shlomo Levi Steinheim: Studies in His Thought (Jerusalem, 1994, p. 198) that he planned to publish the work, but as far as is known, it has not yet appeared.

Incidentally, Edgardo’s Hebrew name, Gad Yosef, was recently found in a handwritten prayer for his rescue, in a manuscript recently acquired by the National Library (Heb. 11598).

I saw the letter about the baptism in Miske during a visit to Budapest as part of the At the Source program. The program aims to promote cooperation between the National Library of Israel and Jewish libraries and archives across Europe. It is organized by the Library’s Gesher L’Europa department and supported by Yad Hanadiv Europe and includes professional workshops in various locations. Alongside the professional training, local librarians present their work, and valuable professional connections are formed. At the Hungarian Jewish Museum in Budapest, staff member Tamás Lózsy showed me the materials he was working on, among them the copy of this letter. I am deeply grateful for his assistance.

In the High Holiday prayers, we often recite the verse: “And I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and you shall be clean.” When read in its biblical context, one can almost feel the refreshing, purifying touch of the water that cleanses a penitent from sin. In Christianity, this same verse became a foundation for the sacrament of baptism – the rite through which a person joins the Church and attains salvation. The New Testament declares: “He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved” (Mark 16:16). But what of those who do not believe and are nevertheless baptized? Can such a baptism have any validity without the person’s consent? From the two stories told here, it seems that, tragically, there were those who believed it could.