William Shakespeare is widely regarded as one of the greatest writers on love in Western literature. So much so that his very name has become shorthand for impassioned, poetic explorations of romance. Romeo and Juliet, Benedick and Beatrice, Lucentio and Bianca, Antony and Cleopatra – and that’s without even mentioning the sonnets.

But is that reputation entirely deserved?

A closer reading reveals that Shakespeare’s so-called love stories are anything but simple. Each relationship is tangled with contradictions, moral dilemmas, and emotional instability. How many of these stories are really about love – and how many are about something else entirely, merely dressed in the language of romance?

One of the clearest examples of this complexity can be found in Antony and Cleopatra.

Written around 1606, roughly a decade before Shakespeare’s death, the play was probably staged the following year. As with most of his works, the text we read today was not printed during Shakespeare’s lifetime, but appears in the collection scholars refer to as “The First Folio” – a large-format volume published seven years after his death, which gathered together most of his plays.

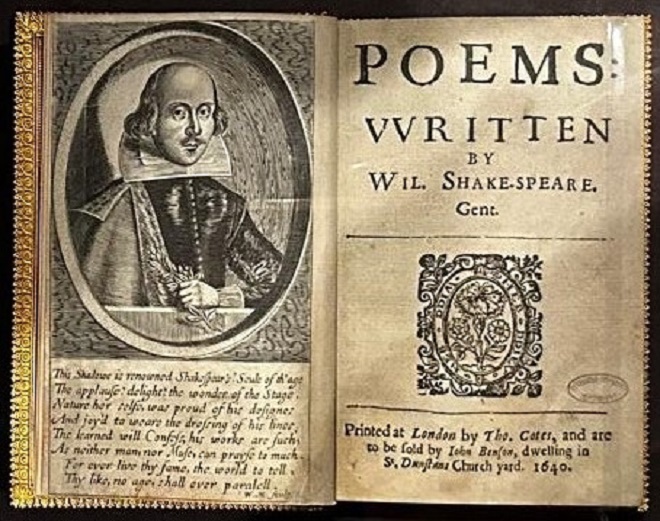

Only 228 complete copies and 158 partial copies of the First Folio survive today. One of them – thanks to a generous donation – is housed in the National Library of Israel. The Library’s conservation staff carefully maintains it alongside other rare Shakespearean editions, including a complete Second Folio and an early volume of his collected poetry and sonnets titled Poems: Written by Wil. Shakespeare, Gent., published in 1640.

The Library’s copy of Poems includes something exceptionally rare: the original title page, featuring a portrait of Shakespeare himself – a page torn out of most copies over the centuries.

Back to Antony and Cleopatra.

Mark Antony – Roman general, celebrated hero, and a member of the triumvirate which ruled Rome after the assassination of Julius Caesar – falls passionately in love with Cleopatra. Many see the affair as a betrayal, but Antony is enthralled by the Egyptian queen, herself once Caesar’s lover. His infatuation is so complete that he neglects his duties as one of the most powerful men in the republic and begins making plans to remain in Egypt.

In Rome, Octavian – who would later be known as Augustus Caesar – is alarmed. The affair threatens Antony’s loyalty to the republic. When appeals and warnings fail, Octavian urges Antony to return and help suppress the growing threat of piracy. As a political gesture, he offers Antony the hand of his sister, Octavia.

Cleopatra is, understandably, furious. But Antony accepts the offer, returns to Rome, and marries Octavia. The marriage proves hollow, and the military campaign ends in disappointment. Disillusioned by Octavian and Lepidus’s treatment of the pirate leader, Antony returns to Egypt. There, he reconciles with Cleopatra, reaffirms their bond, and proclaims himself ruler of the eastern Roman Republic. Together, they prepare for the inevitable war against Rome.

Even a prophecy warning that he will lose does not deter him.

During the decisive naval battle, Cleopatra unexpectedly retreats with her fleet. Antony, rather than hold the line, abandons his position and follows her – choosing love over duty. Though enraged by her apparent misjudgment, the two reconcile and prepare for another confrontation. Once again, Octavian defeats him. This time, Antony blames Cleopatra outright for the failure.

But Cleopatra is no ordinary consort. Instead of begging forgiveness, she stages a fake suicide in an effort to win him back. Still very much in love, Antony hears the false report – and without verifying it, falls on his own sword. He survives the initial blow and is carried, dying, to Cleopatra’s chambers, where he dies in her arms.

After his death, and Octavian’s victory, Cleopatra understands what lies ahead: public humiliation in a Roman triumphal parade. To avoid that fate, she arranges to have a venomous snake brought to her and chooses death on her own terms. The play ends with Octavian standing over the bodies of the two lovers – a mixture of triumph and melancholy – and orders that they be buried together.

The plot draws, in part, from actual history – specifically Parallel Lives by Plutarch, a collection of paired Greek and Roman biographies written not long after the events in question.

The clearest takeaway (as in several other Shakespearean tragedies – Romeo and Juliet, for one) is obvious: don’t fake your own death without telling your partner. The consequences might be irreversible.

But was Shakespeare trying to say something deeper about relationships – not just for his own time, but for generations to come? Was the dynamic between the Roman general and the Egyptian queen truly a tragic love story, or was it a tale of politics, power, and shifting loyalties dressed up as romance?

From Antony’s side, it seems – at least at first – like love. Impulsive and all-consuming, perhaps, but genuine. He abandons Rome again and again for Cleopatra. He walks away from a prestigious political marriage, from power, from his military command – all to be with her.

But from Cleopatra’s side, the picture is more complicated. She may love him at the beginning, begging him not to heed Octavian’s call. But when he leaves her in Egypt and marries Octavia to please his political rival, Cleopatra’s fury is justified – and her priorities shift. When Antony returns, she forgives him, but only once she’s sure she still outranks Octavia in his eyes.

Then comes a turning point. Antony declares himself ruler of Egypt and the eastern Roman Republic – not in partnership, but above her. Cleopatra does not respond with adoration. From that moment, his choices become increasingly reckless, indifferent to her well-being, and ultimately catastrophic. When things fall apart, he blames her.

Later, Cleopatra tries – perhaps overly theatrically – to draw him back by staging a suicide. But she miscalculates: rather than rushing to her side, Antony falls on his sword. It’s not a dramatic reunion – it’s a fatal misstep.

Marcus Antonius at Cleopatra’s Banquet, Gerard Hoet, 18th century

At that moment, Octavian has won. Cleopatra, knowing she is destined to be paraded through Rome as a defeated queen, chooses to take her fate into her own hands. With her attendants, she dies in a deliberately stylized act of self-determination – death by snake. But unlike Antony’s suicide, which feels like surrender, Cleopatra’s is a calculated political gesture. She reclaims her agency, rejecting humiliation and choosing defeat on her own terms. She refuses to be a trophy. Her final act is one of pride and power.

This ending reframes the entire narrative. What looked like love now feels like illusion. Antony treats Cleopatra as a romantic refuge, an escape from duty – a safe haven he assumes will always be there. He expects obedience, even when his commands endanger her and her people. For a time, she complies. But once his choices begin to cost Egyptian lives, she steps away – choosing her crown over a man who has betrayed her.

His suicide – spurred by rumors of her death – isn’t an act of passion, but of fear and collapse. The illusion he’s been clinging to shatters. And so he turns, not to Cleopatra, but to the sword. She has been replaced by a weapon – a final, destructive fantasy.

Cleopatra, by contrast, is a ruler. In an era of political instability and male dominance, she fights from the beginning of her reign to secure her power and protect her nation. She allies with Julius Caesar out of strategic necessity. Later, she partners with Antony in the hope of continuing Roman support for her fragile kingdom. Her loyalty lies not with the man, but with her realm. Her decisions are deliberate, her calculations clear-eyed. She refuses to follow blindly – even into death. Her final act is not surrender, but defiance. She reclaims control from the hands of Roman men.

Antony’s death marks his fall – the loss of Rome to Octavian. Cleopatra’s death transforms her into a legend. She becomes mythic, a symbol of female agency whose image endures across East and West to this day.

Antony saw Cleopatra as fantasy – and when the fantasy cracked, so did he. Cleopatra saw in Antony a path to strength and survival – and when that path failed, she withdrew and took command of her fate. On one side: illusion. On the other: strategy.

Eternal love? Probably not.