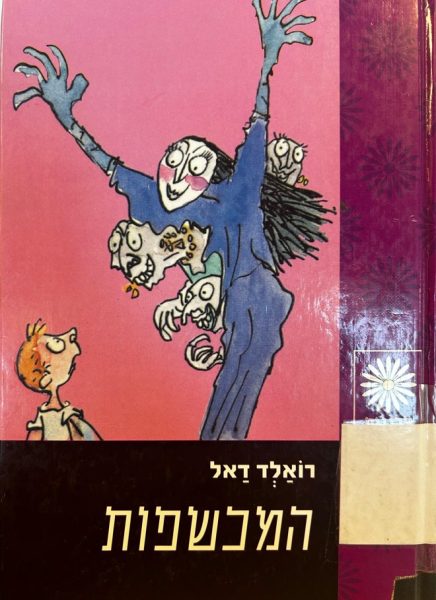

“The most important thing you should know about REAL WITCHES is this. Listen very carefully. Never forget what is coming next.

REAL WITCHES dress in ordinary clothes and look very much like ordinary women. They live in ordinary houses and they work in ORDINARY JOBS. That is why they are so hard to catch.

A real witch hates children with a red-hot sizzling hatred that is more sizzling and red-hot than any hatred you could possibly imagine […]

‘Which child,’ she says to herself all day long, ‘exactly which child shall I choose for my next squelching?’”

A lovely little paragraph to read your child before bed, wouldn’t you say?

This, of course, is the opening passage of The Witches, by Roald Dahl.

Like all of Dahl’s works, this book was published into a world that already knew a variety of children’s literature, including the dark and terrifying kind. Yes, the world had already seen Brothers Grimm-style horror stories, with or without preachy moral conclusions. But Dahl pushed that freedom, the freedom to write for children without restraint, and to shock both them and their parents, as far as it could go.

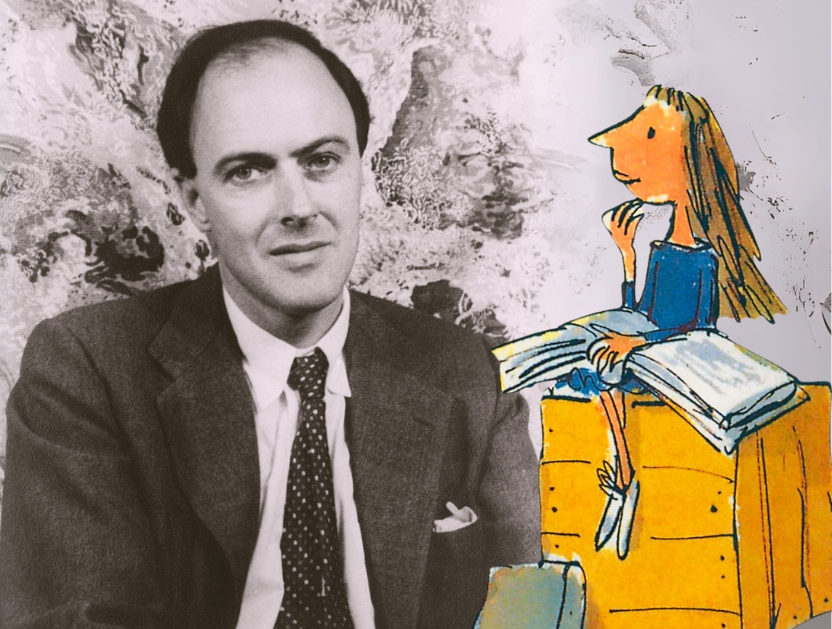

It all began, like most good stories, with a difficult childhood (though “difficult” might be putting it mildly).

Roald Dahl was born in the northern suburbs of Cardiff, the capital of Wales – a lesser-known corner of the United Kingdom. His parents were immigrants from Norway, so his first language was Norwegian. The fairy tales he heard at home were rooted in Norse mythology, populated by witches, elves, and a host of other creatures, both good and evil, sure, but mostly evil.

He didn’t have much time to enjoy his childhood before everything began to unravel. Between the ages of three and four, Dahl lost both his sister and his father. A few years later, he was sent off to boarding school. He attended a number of them – a string of dreadful institutions – each seemingly worse than the last. There he came to understand cruelty: the brutality of schoolyard bullies, and the apathy, or outright abuse, of the adults. Physical punishment, beatings, and borderline torture were routine.

Dahl himself was no innocent. In his memoirs, he gleefully recounts endless pranks, performed alone and with friends. Still, even a boy who slips a dead mouse into the candy jar at the local sweet shop doesn’t deserve the harsh violence he endured.

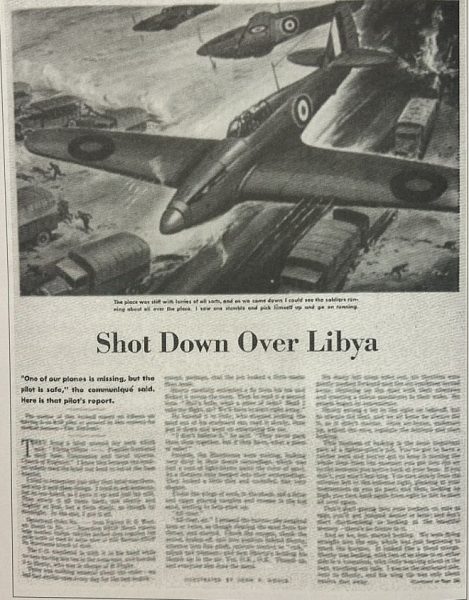

After finishing school, Dahl had no interest in further studies. Instead, he traveled to Africa to work for a major oil company. At that point, his only connection to writing was the drawer in his mother’s nightstand, where she kept the hundreds of letters he had written her over the years he spent away from home. With the outbreak of World War II, Dahl joined the British Royal Air Force. His squadron was stationed in the Middle East. One day, he was forced to make an emergency crash landing. He survived the incident, but sustained serious injuries that would haunt him for years. That crash also marked the start of something else: a writing career. Though he didn’t know it at the time.

After several months of recovery, he was sent overseas to a more relaxed posting, as a military attaché in Washington, D.C. There, among the vibrant expat British community in permissive wartime America, Dahl became something of a celebrity. The dashing, cynical young pilot, who had been dramatically shot down over Africa, full of swagger and war stories. He didn’t shy away from embellishment, and before long, his crash landing had transformed into a heroic tale in which he personally downed a double-digit number of enemy planes before being taken out himself.

One person who heard this tale was the celebrated writer E. M. Forster, who asked Dahl to write down a summary of his experiences so that Forster could turn it into a magazine piece. The text Dahl sent was so vivid, polished, and entertaining that Forster submitted it to the paper exactly as it was – no edits, and under Dahl’s own byline.

“Shot Down Over Libya” appeared shortly thereafter in the Saturday Evening Post. It was a massive success and marked Dahl’s debut as a serious writer.

Around that time, Dahl also wrote a children’s story about “gremlins” – mischievous little creatures that British pilots (and others) blamed for secretly sabotaging aircraft. The story reached a certain Walt Disney, who immediately wanted Dahl to adapt it into a screenplay. The film never materialized, but Disney did publish Dahl’s manuscript as a picture book. Once again, to everyone’s surprise, it was a hit.

After the war, Dahl returned to Britain, where he struggled to find publishers for his macabre stories, which lacked tidy morals and softened edges. He made a living primarily as an art dealer, but he knew this wasn’t his calling. He decided to return to America.

In 1951, at a party hosted by American friends, he met Patricia Neal – a dazzling film star who had already shared a movie set with Ronald Reagan and a bed with Gary Cooper. They fell for each other, or at the very least became deeply intrigued. He was enchanted by her beauty. She was captivated by his wit, cynicism, narcissism, and astonishing storytelling gift.

Their marriage wasn’t especially tender or romantic, neither of them were known for those traits. But while Patricia’s acting career was on the rise, Dahl returned to writing. His stories – sharp, dark, funny, and blunt – were published in various magazines, including several adults-only pieces in Playboy.

His writing for adults, which came before his children’s books, was no less wild or imaginative. Time and again, he confronted readers with their own morality, their prejudices, and the choices they might make if placed, or forced, into particular situations.

When he and Patricia had children, Dahl devoted himself to them completely, for the first time in his life. The cynical, unruly man who often saw the world as a malevolent force discovered a small pocket of light. He began telling his kids bedtime stories and slowly realized that maybe, just maybe, he could write for children.

“Had I not had children of my own,” he later said, “I would have never written books for children, nor would I have been capable of doing so.”

And like almost everything in his life, he did it in a way no one had before, or since.

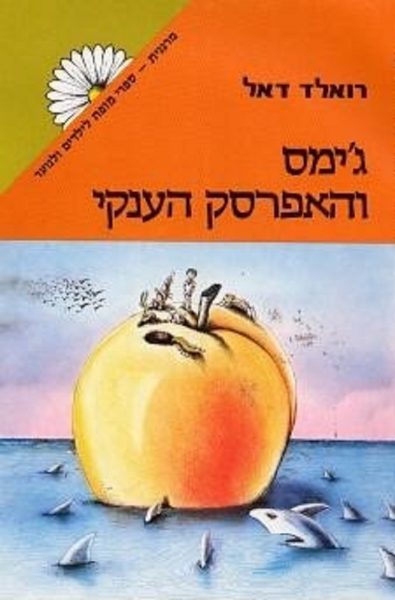

When Dahl sent the draft of James and the Giant Peach to his publisher, he was slightly embarrassed. What was he supposed to do with this strange manuscript? But the editor he worked with predicted it would become a classic, and they decided to publish it anyway. Sales were slow at first, and British publishers flat-out refused to print it. Was it the oversized bugs? The abuse James endures? The grotesque fate of the wicked aunts? Whatever the reason, even after a second book was released, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the British still weren’t interested, and American readers weren’t rushing to stores either.

Once again, it was Walt Disney who gave Dahl his big break. He bought the rights to turn the story of the eccentric millionaire and his bizarre chocolate factory into a film. Initially, Dahl was meant to write the screenplay, but that quickly fell apart. When the studio realized he was impossible to collaborate with, they hired someone else. Dahl came to despise the movie with a passion and made no effort to hide it. But he also enjoyed the results: within months of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory hitting theaters, more than 750,000 copies of the book were sold in the U.S. alone. British publishers finally gave in, and the book was soon translated into many more languages.

It was translated into Hebrew as well, like most of Dahl’s books, despite his unabashed, conspiratorial antisemitism. “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity…even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason,” Dahl told an interviewer in the early 1980s.

A few years later, in 1990, he remarked: “I am certainly anti-Israel, and I have become anti-Semitic…” These comments drew a severe backlash among Jews around the world. Even Jewish children felt a need to respond, as in the case of Aliza Cohen and Tamar Mittman, two young girls who attended the Brandeis-Hillel Day School in San Francisco California, and chose to write the author a letter:

“Dear Mr. Dahl, we love your books but we have a problem… We are Jews! […] Can you please change your mind about what you said about Jews! We like you but we feel that you don’t like us – Love, Aliza and Tamar.”

Dahl sent a reply to the girls and to their classmates who had also written him: “The trouble with many Jewish people in other countries is that they refuse to look at both sides of the coin, and anyone, like me for instance, who dares to raise a voice against Israel is immediately labeled an anti-Semite”.

He was a difficult man, seeing the world through a dark veil that no one could lift.

Meanwhile, his family, the only people with whom he seemed to show a different of himself, were rocked by crisis after crisis, with each one of these taking its toll on Dahl.

When his young son suffered a serious head injury and developed hydrocephalus, Dahl stepped away from writing and collaborated with a neurosurgeon and an engineer to invent an innovative new drainage valve. Eventually named after him, the device went on to save thousands of children’s lives.

When his eldest daughter died at age seven due to complications from measles, Dahl was shattered. He mourned her intensely, almost violently, banning his wife and children from speaking her name.

Later, while pregnant and at the height of her career, Patricia suffered three strokes in quick succession. Doctors doubted she would survive, and if she did, they didn’t expect her to function at even a basic level. But once again, Dahl dropped everything and devoted himself completely to her care. He spent hours by her side and hired a small army of therapists and caregivers to help her recover physically and cognitively.

His efforts paid off. She made a near-complete recovery. Within months, she had landed a new acting role and returned to a full, active life. But did all that sacrifice reignite a spark between them? Something did flare up, but not between Patricia and Roald. Dahl began a passionate affair with another woman, one that would eventually end his marriage and lead him to remarry, later that same year.

Throughout all of this, he kept writing. With his beloved pencils and plain notebooks stacked on his desk. He never could understand how other writers used typewriters. Didn’t they ever need to erase things? Didn’t they keep rewriting and revising their stories until they sparkled, until every line was razor sharp?

Though he continued writing for adults, mostly short stories and memoirs, his heart belonged to children. He felt something for them with an intensity he couldn’t summon for people his own age, for better and for worse.

“Children are a great discipline because they are highly critical,” he once wrote. “And they lose interest so quickly. You have to keep things ticking along. And if you think a child is getting bored, you must think up something that jolts it back. Something that tickles. You have to know what children like.”

Parents and educators actively recoiled from his books, at the grotesque imagery, the detailed accounts of abuse, the racism, the fat-shaming (though the term didn’t exist yet), the horror, and the hatred woven into so many of his pages.

When asked whether it was truly necessary to flatten James’s wicked aunts to death with a giant peach, Dahl replied that he received hundreds of letters from children in which they repeatedly expressed sentiments like ”the bit I liked best was when the aunts get squashed by the peach.”

“Children love to be spooked, to be made to giggle,” he said once in an interview. “They like a touch of the macabre as long as it’s funny too. They don’t relate it to life. They enjoy the fantasy. And my nastiness is never gratuitous. It’s retribution. Beastly people must be punished.”

And indeed, children did love the stories. They asked to hear them over and over, watched the film adaptations and flocked to the stage productions based on them.

“What shocks adults doesn’t shock children,” Dahl once wrote. “You can be as crude as you like – as long as it makes them laugh.”

His stories – grotesque, macabre, terrifying – were also wickedly funny. The villains were often attractive, popular adults or seemingly perfect children. And it worked.

But it didn’t work only because Dahl tapped into some feral instinct or gave kids a safe outlet for their darker thoughts. It worked, and still works, because the stories give them something essential: justice.

Children still love his books because he articulates a truth they’re often not allowed to say aloud: that the adults in their lives are not always good. And that goodness doesn’t always triumph. These stories aren’t just fantasy, they feel painfully real. The villains are unmistakably wicked, and by the end, they get what they deserve, in ways that are gloriously satisfying.

Justice.