Could Arab, Persian, and Islamic artistic influences have shaped the appearance of Jewish manuscripts, even those of the Bible itself?

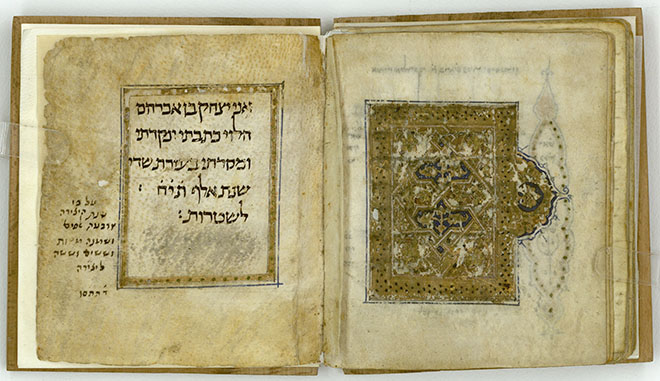

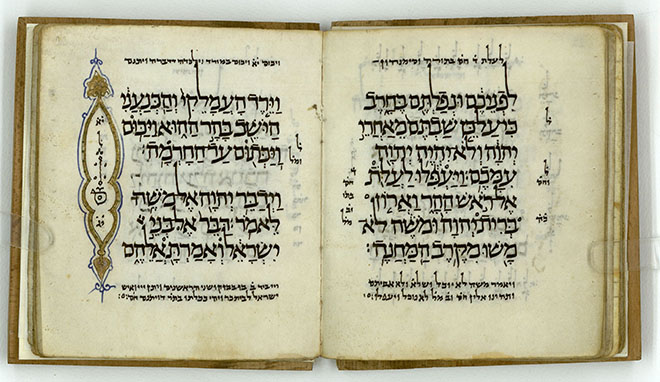

The book we hold is small and delicate, its thin pages requiring special care. At first glance, one might think it a Muslim manuscript, as the opening page is decorated with a typical “carpet-style” design. But by the second page it is clear that this is not the case. It is a part of the Hebrew Bible, specifically Parashat Shelach Lecha, the fourth portion in the Book of Numbers (chapters 13-15).

This small volume holds within it the story of a vibrant Jewish community and the ways in which it preserved Jewish tradition.

“…Excellent grammar and commentary came forth from Isfahan,” wrote Sahal ben Mazliach, a 10th-century Karaite commentator from Jerusalem, in his commentary on Genesis. His words point to the early engagement with biblical study among the Jews of Iran. For generations, the Bible held a central place in the religious and cultural life of Iranian Jewry. It was often translated into Judeo-Persian and adapted into various literary forms.

Although this manuscript is written in Hebrew rather than Judeo-Persian, certain stylistic features and the names of individuals mentioned in it suggest that it originated in one of Iran’s Jewish communities.

In 1106–1107 CE (corresponding to the year 1418 in the ancient Persian calendar), Yitzhak ben Avraham HaLevi completed the preparation of this manuscript.

Who was Yitzhak ben Avraham HaLevi? While not known from other sources, it is likely that he was a professional scribe, given the precision of his work and his fidelity to Jewish tradition. He was not merely a copyist. As noted in the manuscript’s colophon, he also added vocalization marks, cantillation marks, Masorah Magna, and Masorah Parvah. He carefully marked the sedarim according to the ancient triennial reading cycle once used in the Land of Israel.

In many ways, this manuscript reflects ancient Jewish customs and traditions passed down through generations. At the same time, it also incorporates elements that were considered modern for its day, borrowed from Arabic and Persian manuscript traditions. It is clearly a product of the broader Muslim cultural environment in which it was created. Its decorations resemble those found in contemporary Qurans, and the carpet pages at the beginning and end are features commonly seen in Islamic manuscripts.

It is even possible that the practice of dividing the Torah into individual portions was influenced by Quranic traditions, in which the text was often divided into 30 parts for monthly recitation, or into seven parts for weekly reading.

Based on the style of the decorations, scholars believe the manuscript originated in Iran. In the early 20th century, it was in the possession of a man named Nataniel ben Avraham. Beneath his name is a note in Judeo-Persian recording the sale of the book to a man named Menashe on Friday, the 5th of Tevet, 5670 (January 15, 1910).

A similar manuscript, containing Parashat Shoftim, also copied by Yitzhak ben Avraham that same year, was later found in the city of Mashhad. We know of its existence thanks to Professor Amnon Netzer, whose archive is preserved here at the National Library. In the 1970s, while serving as an emissary of the Jewish Agency to Iran, Netzer visited Mashhad. He reported the manuscript to the Library’s chief librarian at the time, Professor Malachi Beit-Arie. A note with this report is still preserved today in Netzer’s archive at the Library.

Like many manuscripts from Iran and other parts of the Middle East, this one eventually found its way to the West in modern times. Its last known owners were Avraham and Anna Tulin, who donated the manuscript to the Jewish National and University Library in 1951.

Today, it is preserved in the Library’s archives, alongside many other manuscripts from across the world and from various periods in history, all containing the same words, the words of the Jewish Torah.