When Alfred Uhry was 10 years old and first allowed to ride Atlanta’s city buses alone, he’d go to libraries to read about a crime so notorious as to both seize his curiosity and hush his relatives.

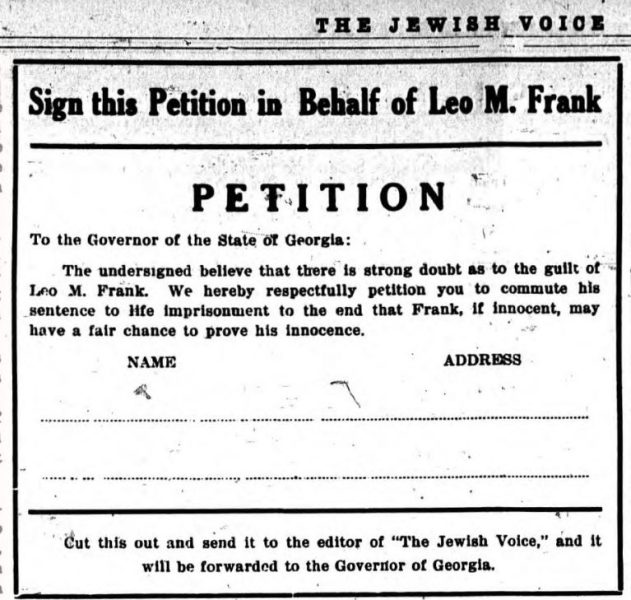

The crime was the lynching three decades earlier of Leo Frank, a Jewish man, on August 17, 1915. The incident occurred after Georgia’s governor commuted Frank’s death sentence to life imprisonment following his conviction in the murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old employee of the firm he managed, the National Pencil Company.

The lynching of Frank happened in Phagan’s hometown of Marietta, Georgia, about a 150-mile drive (241 km.) from the prison in Milledgeville from which he was abducted by the lynch mob. He was taken in a circuitous route and eventually hanged about 20 miles (32 km.) from the factory on Atlanta’s South Forsyth Street where Phagan was found dead on April 27, 1913.

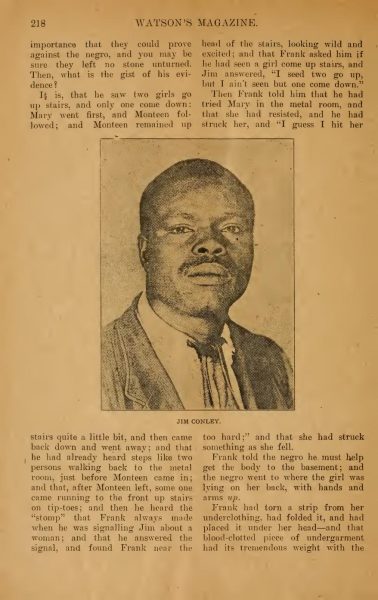

Frank was convicted largely on the testimony of another employee, Jim Conley. Frank’s attorney argued in court that Conley committed the murder and framed Frank. Nearly seven decades later, Alonzo Mann, who as a teenager worked at the pencil company, told reporters from Nashville’s Tennessean newspaper in 1982 that he witnessed Conley moving Phagan’s limp body and that Conley warned him to remain silent about the matter. Mann stated his belief that Conley, not Frank, had killed the girl.

The Frank trial and lynching was tinged with anti-Jewish and anti-northern fervor, often stirred up in southern newspapers at the time; Frank was raised and educated in New York. It also served to reinvigorate the racist group the Ku Klux Klan and led the Jewish fraternal group B’nai B’rith to form the Anti-Defamation League.

And it shook many Jews in Georgia, most of whose ancestors had settled there before the Civil War. Sue Tancill, Uhry’s childhood friend — like him, she is 88 years old — said that her grandparents relocated from Atlanta to Birmingham, Alabama, during the trial out of fear, “when all that antisemitism was going on.”

“For a long time, no one would talk about it because it was such a horrible thing that went on. He was unjustly accused,” said Tancill, who is related to Frank’s widow, Lucille Selig Frank, an Atlanta native. Like two other relatives of Lucille Frank who were interviewed for this article, Tancill isn’t sure what the family connection is.

“No one talked about it. I had to figure it out for myself,” Uhry, in a phone interview from his apartment in Manhattan, said of his early interest in Frank. “It was explosive. I looked it up. It seemed very dramatic.”

He added: “I thought I’d write about it someday.”

And that’s what Uhry, who went on to an accomplished career as a playwright, did. He’d earned a Pulitzer Prize, an Academy Award and two Tony Awards for penning the screenplays to both the stage version and film of Driving Miss Daisy, the first in a trilogy about Uhry’s roots in Atlanta in a Reform Jewish family. The last of the three plays was Parade, a musical about the Frank case.

Parade first was performed on Broadway in 1998. A new American production was mounted earlier this year and will conclude at Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center in September. A Jewish museum in Atlanta, The Breman, in July hosted a panel discussion on the Frank case.

Several experts interviewed for this article stated, without prompting, that the Frank episode remains highly relevant today given the anti-Jewish hatred that’s deepening in certain pockets of the United States.

“This is not entirely new. Antisemitism has always been here. Leo Frank is part of the long cycle of antisemitism,” said Mark Bauman, an Atlanta-area historian of Jews of the southern United States who grew up in New York City.

As to Parade’s revival and The Breman’s panel discussion, Bauman said, “I don’t think [Frank] ever left the consciousness very much.”

The scandal touched non-Jewish Atlantans, too. One, Steve Oney, wrote perhaps the definitive book about the case, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank, published in 2003. He spent 15 years researching and writing the book, an outgrowth of his Esquire article in 1985. For the article, he met with Mann three months before Mann’s death.

Frank’s conviction and lynching must be considered, Oney said, in the context of the circumstances and the times. “It was a very polarizing incident that pitted north versus south, Jew versus gentile, black versus white,” said Oney, who now lives in Los Angeles. “It was extremely volatile. All the ingredients were there for misunderstanding and fear — a toxic mix of ingredients that went into the Leo Frank case.”

In light of Mann’s revelation, Frank’s advocates applied for a posthumous pardon. Georgia’s pardon and parole board ruled against it. The board would grant the second application, but without exonerating Frank of the crime. Its ruling affirmed that the board wasn’t taking a position on Frank’s guilt or innocence and stated that its pardon recognized that the state failed to protect Frank and didn’t arrest those who killed him. It issued the pardon, it said, “to heal old wounds.”

Oney sees parallels today. The American south in Frank’s day was convulsed by the shift from agrarianism to industrialization. Today in the United States, “the Industrial Age has essentially ended and the Information Age is gripping us,” he said. “There’s a tremendous instinct to blame Jews at a moment of cultural inflection.”

Writer-editor Hillel Kuttler can be reached at [email protected].