In the first two decades of British rule in the Land of Israel, Jerusalem grew and flourished. New neighborhoods were established, and institutions of government, education and culture were built. It was a formative, even transformative period, during which a new Jewish city began to take shape outside the Old City walls: impressive, vibrant and full of life.

As Jerusalem expanded, the Old City gradually lost its centrality, and many of its Jewish residents left for the new neighborhoods. The shift was driven partly by the appeal of these new areas, but also by escalating tensions between Jews and Arabs, which peaked in the 1929 riots and later during the Arab Revolt of 1936 to 1939. These events pushed many Jews to relocate to places where Arabs did not live.

Under these circumstances, two main Jewish populations remained in the Jewish Quarter: ultra-Orthodox families who attached value to living specifically within the Old City, and residents of limited means who, because of poverty, could not afford to live elsewhere. Even within this group, socioeconomic levels varied. Some were poor but capable of paying rent for a modest, decent dwelling. Others, the poorest of all, were forced to live in rooms belonging to the charitable endowments run by the Sephardi Community Council.

These endowment houses belonged to two categories. Some were built or purchased by the council using donated funds earmarked for the city’s poor. Others were existing homes bequeathed to the council, often by elderly individuals without heirs who had lived in them.

Typically, poor residents were allowed to reside in these homes for a three-year period, after which they were expected to vacate them for others. In practice, many remained far longer, either because they could not afford alternative housing or because their family lineage granted them a de facto claim to the property.

Moshe David Gaon was a historian and scholar of Eastern Jewish communities and of the Jewish population in the Land of Israel. His name is familiar to many through his son, the popular Israeli singer Yehoram Gaon; his other son was the businessman Benny Gaon. During the Mandate years, Moshe David Gaon served as secretary of the Sephardi Community Council in Jerusalem, whose central responsibilities included supervising and maintaining communal property.

As part of his role, Gaon toured the poorest neighborhoods in and around the Old City in the late 1930s and early 1940s. These visits, conducted on behalf of the council to assess the condition of its endowment properties, resulted in several reports. Preserved in his personal archive, they were recently uncovered during cataloging and digitization work in the National Library of Israel’s Archives Department.

More than eighty years later, these reports offer a rare and fascinating glimpse into life in Jerusalem’s Jewish slum neighborhoods during the Mandate period. Here are several examples from the reports that were uncovered:

The Old City: Ruined and Broken Rooms

The first neighborhood described lay in what was considered the “backyard” of Jerusalem, at the far edge of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City, within a complex of four Sephardi synagogues and adjacent to the Batei Mahse apartment building dating to the 19th century. The rooms in this neighborhood were originally built for the city’s poor residents, especially widows, which is why one of its courtyards was called Hatzar Gvul Almana – “Widow’s Border Court.” Nearby were additional courtyards -the Raban Yohanan ben Zakkai Synagogue, the Istanbul Synagogue, the Talmud Torah Court, and the Rabbinical Court. The neighborhood was established in this area partly because it was already notorious for the foul smells drifting from the tanners’ market and the slaughterhouse that operated there. The area also frightened Jerusalem’s residents due to its proximity to the lepers’ quarter – Jerusalem’s backyard indeed. The lepers lived there until they were expelled from the city, first to the Silwan area, and later to the Hansen Leper Hospital in Talbiya.

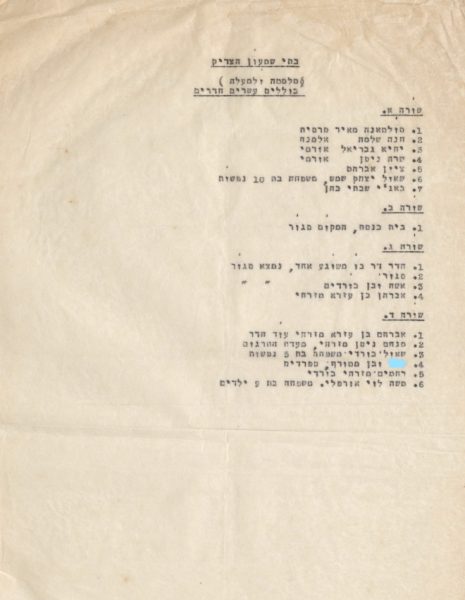

Gaon’s report stated that the compound contained seventy-three rooms. Some were described as so ruined and broken that they were unfit for habitation. The remaining rooms were also in poor condition. Many showed severe dampness, and some lacked windows and doors. Entire families crowded into these rooms, alongside widows and “deserted women” (agunot) who had been denied divorce by their husbands. Also present were the mentally ill, elderly people, the blind and the sick, many of whom belonged to the Kurdish Jewish community.

Shiloah: Jackals and Cave-ins

The city’s large population of poor residents left little alternative. The endowment homes in the Old City were filled to capacity, and many impoverished Jews were forced to leave to areas on the periphery. One example was the Jewish neighborhood known as Shiloah, located in the Arab village of Silwan southeast of the Old City, where many poor Jews lived, most of them Yemenite.

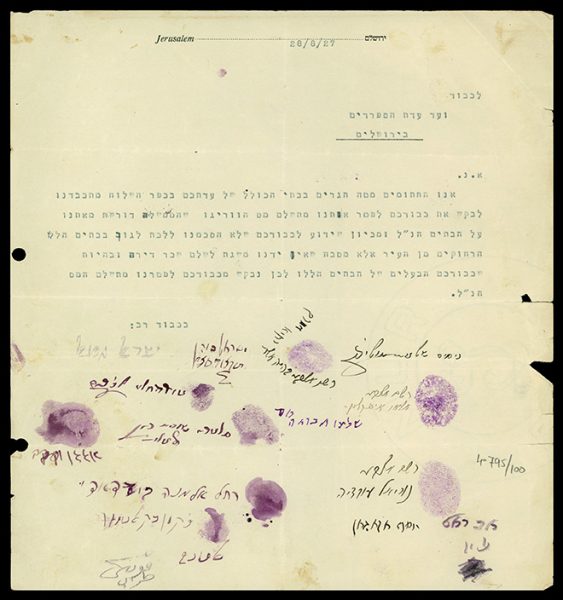

Until 1929, the neighborhood’s overall condition was relatively reasonable. It had a synagogue, a school, a kindergarten, a functioning clinic and even a telephone. Yet many of the residents lived in endowment homes and could not always pay taxes. On June 26, 1927, for example, residents of the endowment houses sent a petition to the Sephardi Community Council, the property owners, requesting an exemption from a property tax on immovable assets. They argued that they did not live in these distant homes by choice but out of necessity, since they could not afford to rent elsewhere.

The situation in Shiloah deteriorated sharply after the 1929 riots. Many Jews abandoned the neighborhood. The few who remained, about twenty families, pleaded with the authorities and with the leaders of the Sephardi Community Council for security and protection, but their appeals went unanswered. In a letter dated January 10, 1938, Aharon Maliakh, the neighborhood’s mukhtar (leader), asked the council to repair the water cistern, which was on the verge of total collapse, along with the gutters that had broken and caused dampness and cave-ins inside the homes. He also described how the area near the cistern attracted jackals that made their way into the houses themselves. The appeals continued until the summer of 1938. It was then that the British police evacuated their post in the village and issued an evacuation order to the Jewish residents, after which the last Jews left the area.

Nahalat Shimon: No Toilet in the Entire Neighborhood

Endowment homes were also maintained in the Nahalat Shimon neighborhood, which lay north of the Old City near the village of Sheikh Jarrah, adjacent to the tomb of Simon the Just (Shimon HaTzadik). The neighborhood was founded in the late 19th century using donations from Jews in North Africa and Gibraltar, collected by Rabbi Shlomo Suzin. Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews lived in its endowment homes. They generally enjoyed good relations with their Arab neighbors, benefited from proximity to the main road and from being near the tomb and its visiting pilgrims, yet the condition of the houses was extremely poor. Gaon’s visit to the endowment homes in Nahalat Shimon left him deeply shaken. He described the situation as follows:

““Opposite the synagogue there is a very large pit that endangers the children of the neighborhood and even the adults, despite their caution. It now serves as a garbage trench, a gaping chasm filled with old cans and every imaginable type of refuse and filth. Only a few days ago, a ten-year-old boy fell in and nearly broke all his bones…

The synagogue suffered greatly during the recent disturbances. All of its furnishings were looted, and its wooden fixtures were torn out. The walls are covered in patches of mold from the roof, which always leaks and may soon collapse unless it is repaired quickly.

There is not a single toilet in the entire neighborhood – for the twenty dwelling rooms there is none at all. As a result, piles of human waste are visible everywhere one steps. Neglect is evident in all directions: broken fences, crumbling walls, roofs without tiles, and doors and windows full of rot.”

Mishkenot Sha’ananim: Two Rooms, a Kitchen and a Plot of Land

The final neighborhood Gaon visited in his tours was Mishkenot Sha’ananim, located west of the Old City and perhaps the most famous of all. The condition of the neighborhood and the lives of its residents had fluctuated since its establishment in 1860, when Moses Montefiore sought to settle Jews there, until its later development in our current day, into a center of culture and art. During the Mandate period, the neighborhood was in good condition. It was relatively spacious compared to other neighborhoods, and a public garden was later built near the famous windmill erected by Montefiore, which still stands today.

The endowment homes in Mishkenot Sha’ananim were generally well maintained. Some even consisted of two rooms and a kitchen, unlike the endowment dwellings in other neighborhoods, which usually consisted of a single room. The houses were accompanied by small plots of land in which residents grew vegetables. The Sephardi Community Council earned about 150 Palestine pounds a year in rent from these homes, which enabled the council to support poorer residents elsewhere in the city.

Over the years, however, the neighborhood’s condition declined due to ongoing neglect. On the one hand, the council did not require residents to sign proper rental contracts and did not repair defects in the homes. On the other hand, perhaps as a result of this laxity, some residents stopped paying rent altogether. Matters deteriorated to the point that the council managed to collect only thirty-eight Palestine pounds in rent for an entire year.

The writer Yaakov Yehoshua, who grew up as a child in nearby Yemin Moshe, remembered this not as negligence but as compassion. His uncle, Moshe Cuenca, was responsible for collecting rent from the tenants of Mishkenot Sha’ananim in exchange for a commission. Yehoshua recalled that his uncle once told a woman who had fallen behind on payments: “This year my earnings have turned into a loss. I have one request. I do not wish to force you to leave the home you live in. Please agree to move into a smaller dwelling.” Years later, when she was elderly, the woman told Yehoshua: “Your uncle took pity on me and my children and could not bring himself to make me leave my home.”

Despite essentially being slums, the places Gaon visited left a lasting imprint on their residents, for better and for worse. Many who grew up in these neighborhoods carried nostalgic childhood memories. Several natives later published their recollections, such as Yonah Cohen, who described life in Nahalat Shimon in his book Hakham Gershon of Nahalat Shimon [Hebrew]. Their testimonies reveal that despite the harsh conditions, many residents loved their homes and their neighborhoods, and a spirit of goodwill and mutual responsibility prevailed. In the end, all residents were forced to leave their homes: some because of evacuation orders issued by the British Mandate or later by the State of Israel, others due to pressure and attacks from Muslim neighbors, and still others during the War of Independence, when their neighborhoods fell, together with the rest of the Jewish Quarter, to the Arab Legion.

The Moshe David Gaon Archive was cataloged and made accessible at the National Library thanks to the kind donation of the Samis Foundation, Seattle, Washington, dedicated to the memory of Samuel Israel.

Arik Kitsis is the archivist responsible for the Moshe David Gaon Archive at the National Library of Israel.